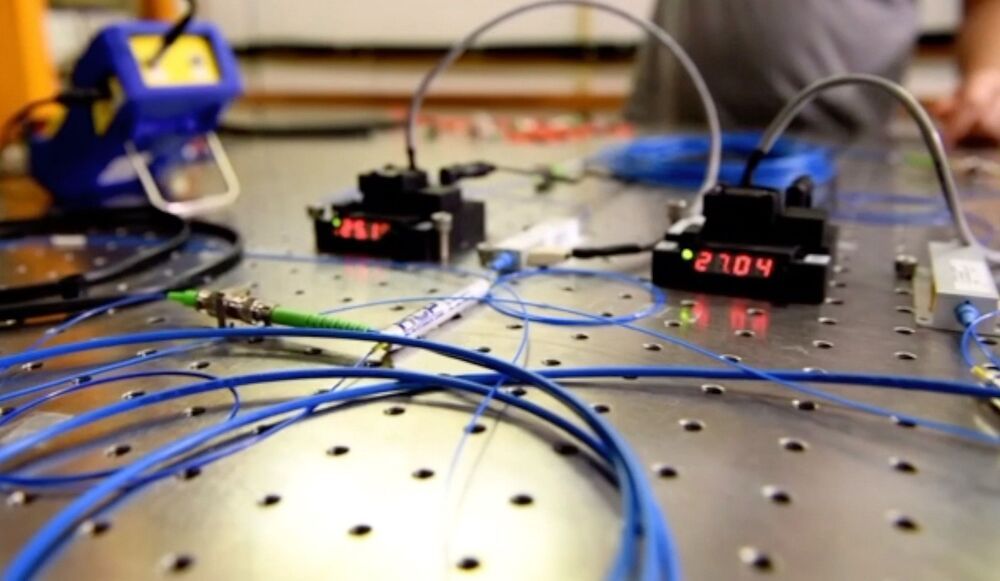

Quantum key distribution is one kind of important cryptographic protocols based on quantum mechanics, in which any outside eavesdropper attempting to obtain the secret key shared by two users will be detected. The successful detection comes from Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle: the measurement of a quantum system, which is required to obtain information of that system, will generally disturb it. The disturbances provide two users with the information that there exists an outside eavesdropper, and they can therefore abort the communication. Nowadays, most people need to share some of their private information for certain services such as products recommendation for online shopping and collaborations between two companies depending on their comm interests. Private Set Intersection Cardinality (PSI-CA) and Private Set Union Cardinality (PSU-CA), which are two primitives in cryptography, involve two or more users who intend to obtain the cardinalities of the intersection and the union of their private sets through the minimum information disclosure of their sets1,2,3.

The definition of Private Set Intersection (PSI), also called Private Matching (PM), was proposed by Freedman4. They employed balanced hashing and homomorphic encryption to design two PSI protocols and also investigated some variants of PSI. In 2012, Cristofaro et al.1 developed several PSI-CA and PSU-CA protocols with linear computation and communication complexity based on the Diffie-Hellman key exchange which blinds the private information. Their protocols were the most efficient compared with the previous classical related ones. There are also other classical PSI-CA or PSU-CA protocols5,6,7,8. Nevertheless, the security of these protocols relies on the unproven difficulty assumptions, such as discrete logarithm, factoring, and quadratic residues assumptions, which will be insecure when quantum computers are available9,10,11.

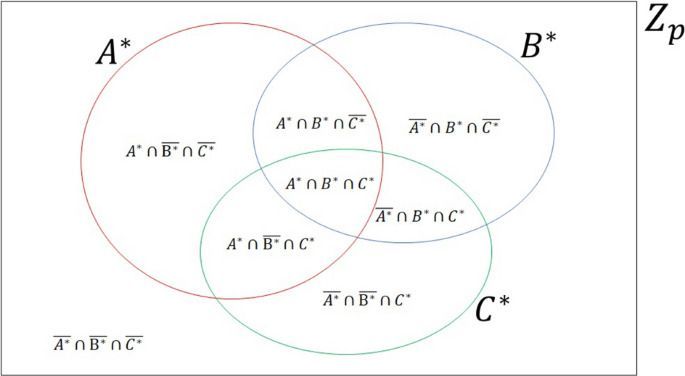

For the sake of improving the security of PSI-CA protocols for two parties, Shi et al.3 designed a probabilistic protocol where multi-qubit entangled states, complicated oracle operators, and measurements in high N-dimensional Hilbert space were utilized. And the same method in Ref.3 was later used to develop a PSI-CA protocol for multiple parties12. For easy implementation of a protocol, Shi et al.13 leveraged Bell states to construct another protocol for PSI-CA and PSU-CA problems that was more practical than that in Ref.3. In both protocols Ref.3 and Ref.13, only two parties who intend to get the cardinalities of the intersection and the union of their private sets are involved. Although Ref.12 works for multiple parties, it only solves the PSI-CA problem and requires multi-qubit entangled states, complicated oracle operators, and measurements. It then interests us that how we could design a more practical protocol for multiple parties to simultaneously solve PSI-CA and PSU-CA problems. Inspired by Shi et al.’s work, we are thus trying to design a three-party protocol to solve PSI-CA and PSU-CA problems, where every two and three parties can obtain the cardinalities of the intersection and the union of their respective private sets with the aid of a semi-honest third party (TP). TP is semi-honest means that he loyally executes the protocol, makes a note of all the intermediate results, and might desire to take other parties’ private information, but he cannot collude with dishonest parties. We then give a detailed analysis of the presented protocol’s security. Besides, the influence of six typical kinds of Markovian noise on our protocol is also analyzed.