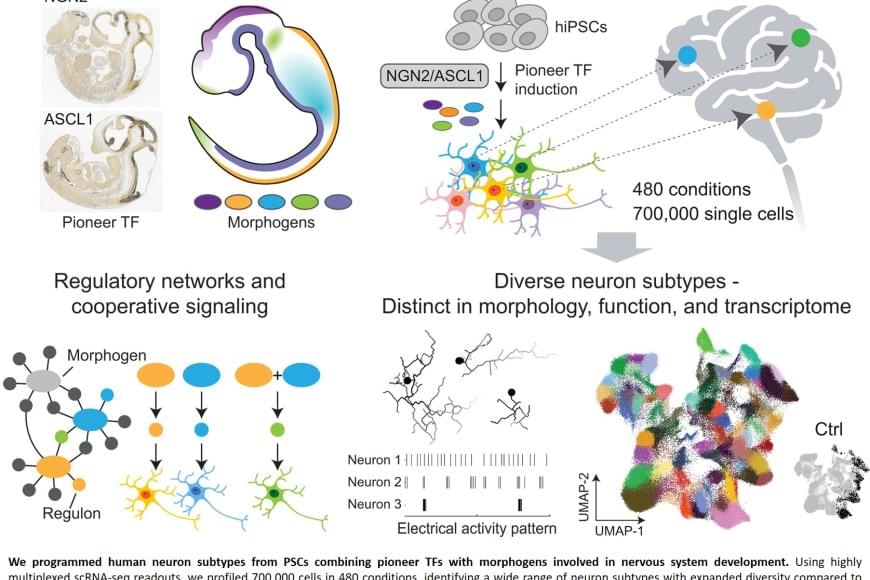

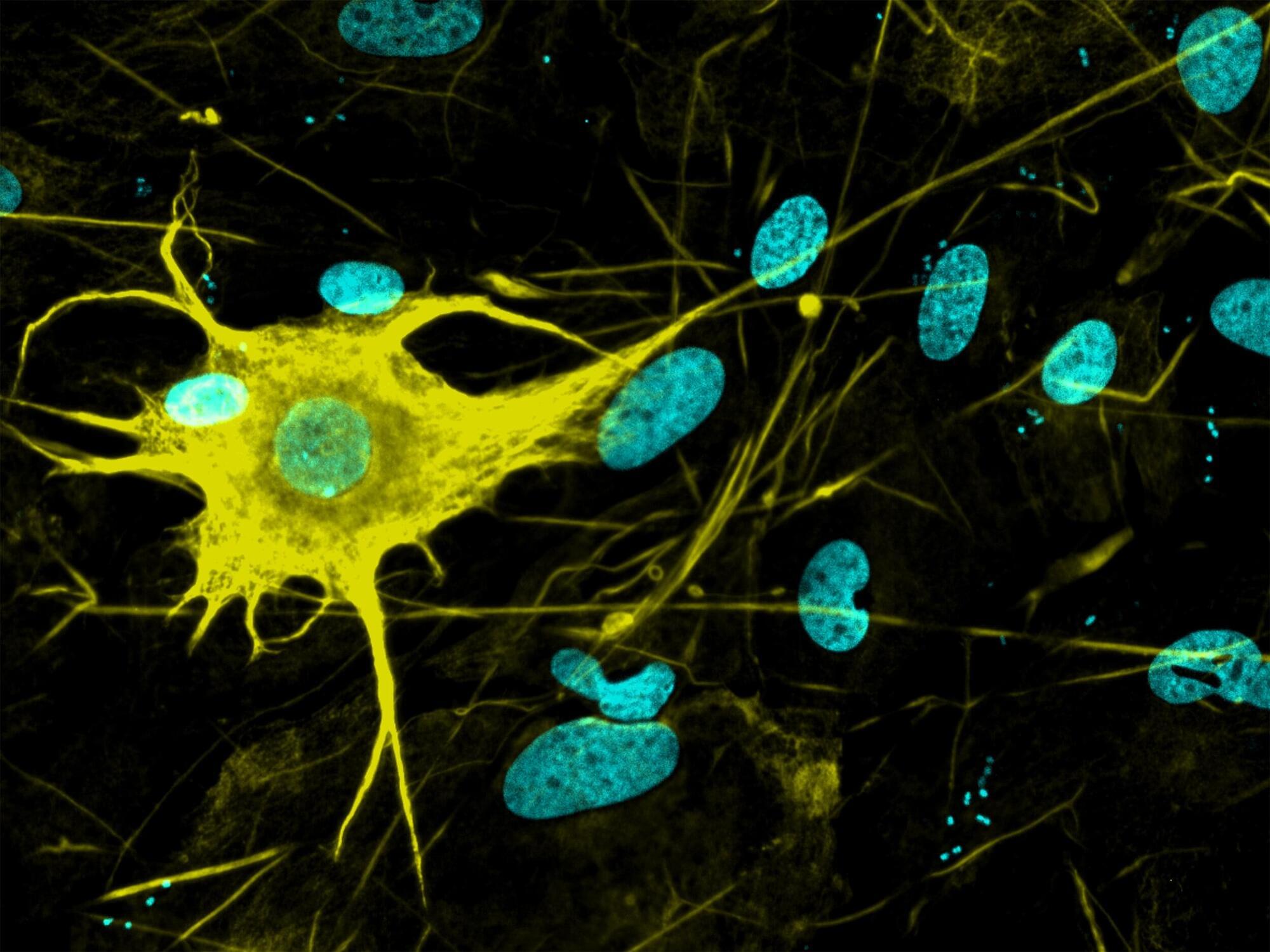

Nerve cells are not just nerve cells. Depending on how finely we distinguish, there are several hundred to several thousand different types of nerve cell in the human brain according to the latest calculations. These cell types vary in their function, in the number and length of their cellular appendages, and in their interconnections. They emit different neurotransmitters into our synapses and, depending on the region of the brain – for example, the cerebral cortex or the midbrain – different cell types are active.

When scientists produced nerve cells from stem cells in Petri dishes for their experiments in the past, it was not possible to take their vast diversity into account. Until now, researchers had only developed procedures for growing a few dozen different types of nerve cell in vitro. They achieved this using genetic engineering or by adding signalling molecules to activate particular cellular signalling pathways. However, they never got close to achieving the diversity of hundreds or thousands of different nerve cell types that actually exists.

“Neurons derived from stem cells are frequently used to study diseases. But up to now, researchers have often ignored which precise types of neuron they are working with,” says Barbara Treutlein, Professor at the Department of Biosystems Science and Engineering at ETH Zurich in Basel. However, this is not the best approach to such work. “If we want to develop cell culture models for diseases and disorders such as Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s and depression, we need to take the specific type of nerve cell involved into consideration.”

For the first time, researchers at ETH Zurich have successfully produced hundreds of different types of nerve cell from human stem cells in Petri dishes. In the future, it will thus be possible to investigate neurological disorders using cell cultures instead of animal testing.