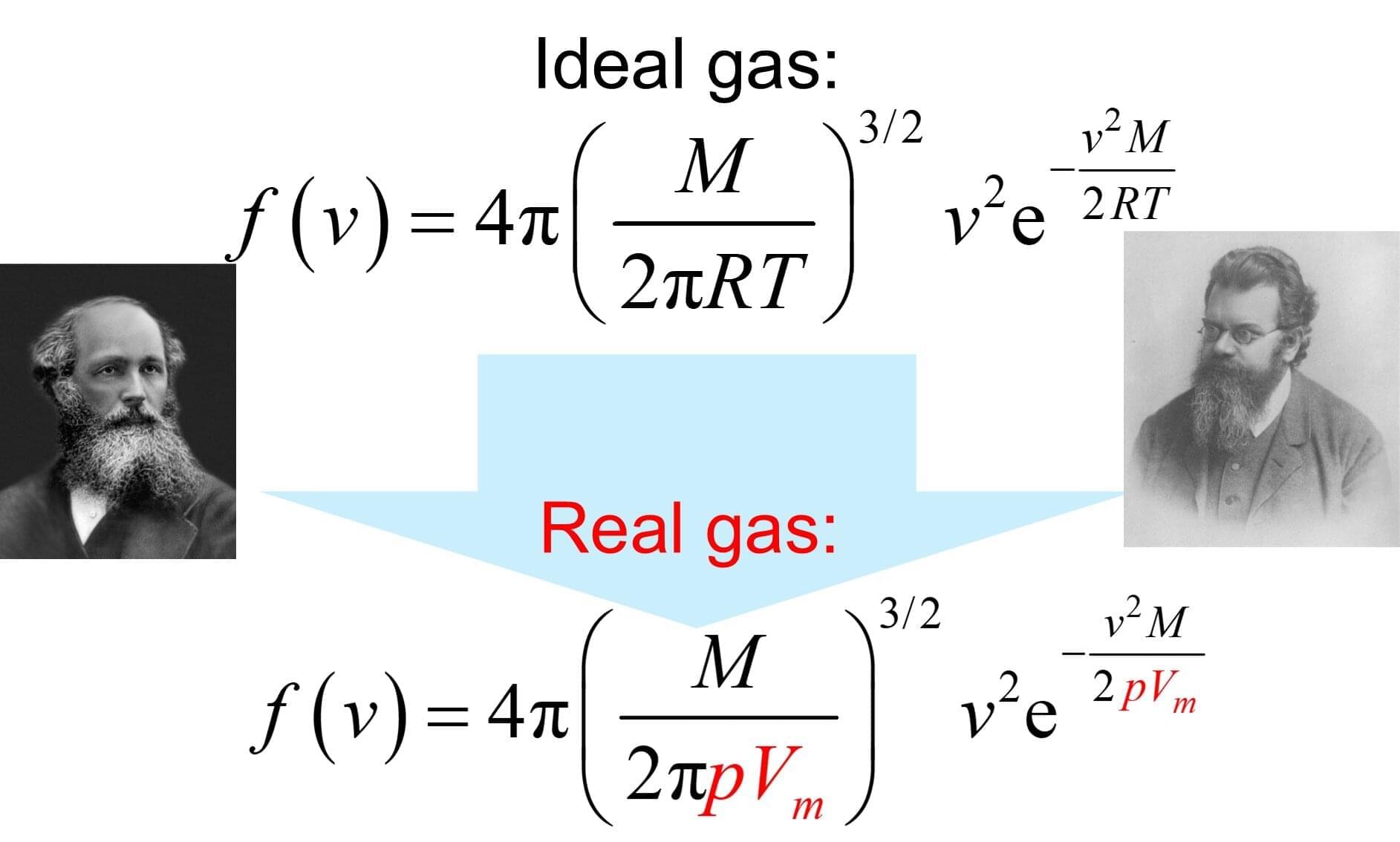

The Maxwell–Boltzmann distribution describes the probability distribution of molecular speeds in a sample of an ideal gas. Introduced over 150 years ago, it is based on the work of Scottish physicist and mathematician James Clerk Maxwell (1831–1879) and Austrian mathematician and theoretical physicist Ludwig Boltzmann (1844–1906).

Today, the distribution and its implications are commonly taught to undergraduate students in chemistry and physics, particularly in introductory courses on physical chemistry or statistical mechanics.

In a recent theoretical paper, I introduced a novel formula that extends this well-known distribution to real gases.