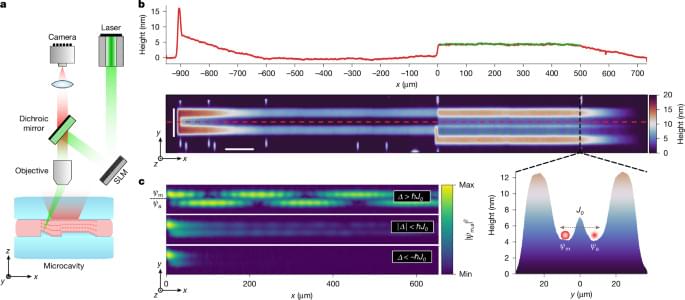

Two independent groups optimize diamond-based quantum sensing by using more than 100 such sensors in parallel.

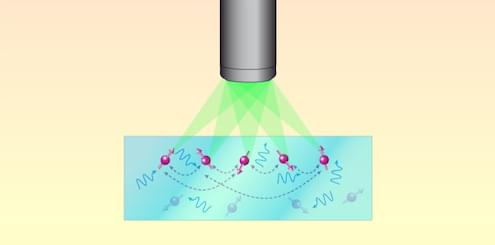

Diamond has long been prized for its beauty, and it holds the record as the hardest known natural material. By introducing nitrogen atoms into its crystal lattice, it can also be transformed into a remarkable quantum sensor. The associated crystal defects are known as nitrogen-vacancy (NV) centers, and they imbue such sensors with unprecedented electromagnetic-field sensitivity and excellent spatial resolution [1]. However, experimental platforms designed to exploit these sensors have so far had limited applicability because the sensing speed and resolution are difficult to simultaneously optimize. Now two research teams—one led by Shimon Kolkowitz at the University of California, Berkeley, [2] and the other by Nathalie de Leon at Princeton University [3]—have independently developed a way of manipulating and measuring more than 100 NV centers in parallel (Fig. 1).