Dr. John Swierk: “This is also the first study to explicitly look at inks sold in the United States and is probably the most comprehensive because it looks at the pigments, which nominally stay in the skin, and the carrier package, which is what the pigment is suspended in.”

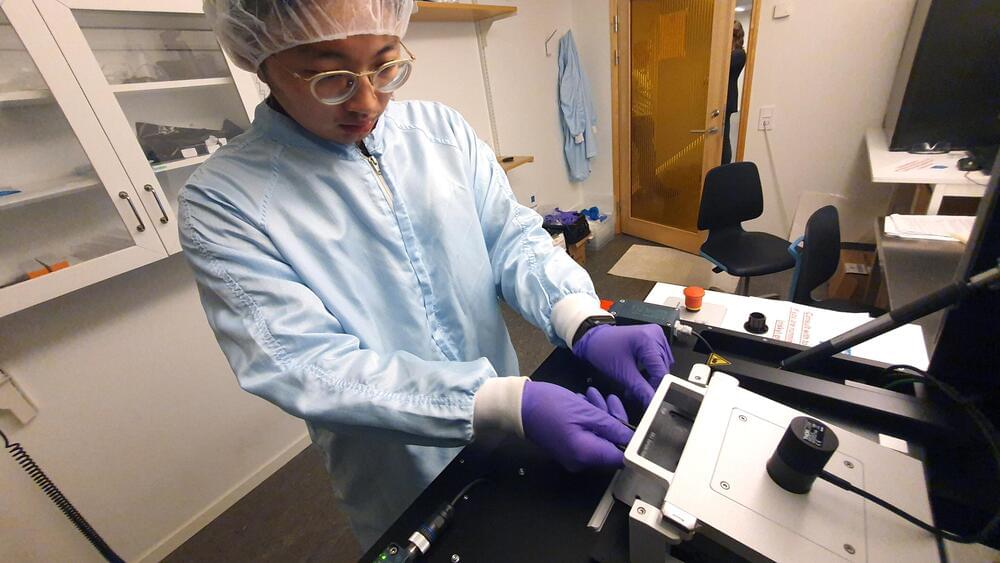

Do the ingredients in tattoo inks match the labels on their respective bottles? This is what a recent study published in Analytical Chemistry hopes to address as a team of researchers from Binghamton University investigated the accuracy of ink ingredients and what’s labeled on their containers. This study holds the potential to help scientists, artists, and their customers better understand the health risks, to include allergic reactions and other risks, of using the wrong ink ingredients for tattoos.

For the study, the researchers examined ingredients from 54 inks emanating from nine common brands within the United States with the goal of ascertaining their exact chemical compositions compared to what was labeled on their respective bottles. In the end, the researchers identified that 45 of the 54 inks possessed a myriad of pigments and/or additives that were not properly labeled on the bottles that could pose health risks to customers receiving ink tattoos, including allergic skin reactions and other long-term health risks, including non-skin-related risks, such as cancer. Despite the alarming findings, the researchers could not ascertain which unlisted ingredients were intentionally or accidentally added to the inks.

This study comes as Congress passed the Modernization of Cosmetics Regulation Act (MoCRA) in 2022, which grants the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) first-time power to monitor tattoo ink ingredients and their labels. Until MoCRA, the cosmetic industry was almost entirely unregulated.