It’s all thanks to a titanium beam.

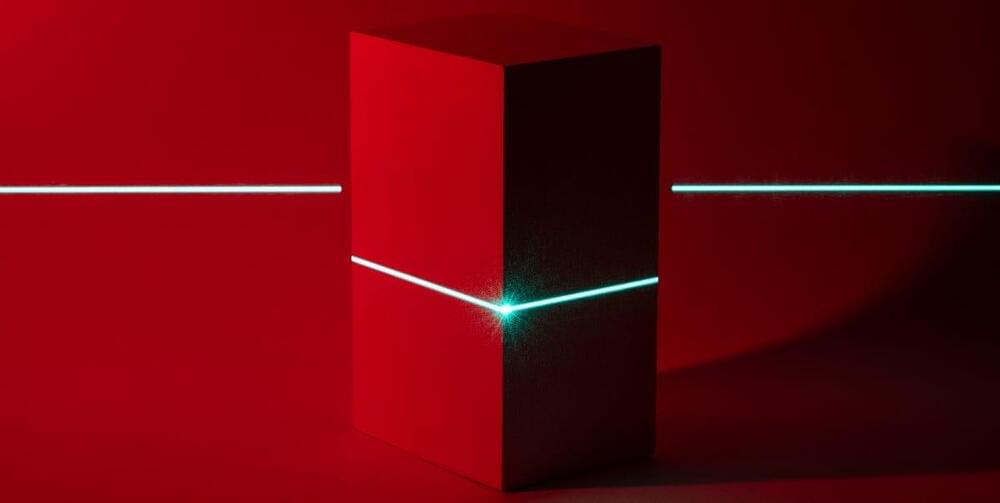

In a study published in Device (“Self-powered electrostatic tweezer for adaptive object manipulation”), a research team led by Dr. DU Xuemin from the Shenzhen Institute of Advanced Technology (SIAT) of the Chinese Academy of Sciences has reported a new self-powered electrostatic tweezer that offers superior accumulation and tunability of triboelectric charges, enabling unprecedented flexibility and adaptability for manipulating objects in various working scenarios.

The ability to manipulate objects using physical tweezers is essential in fields such as physics, chemistry, and biology. However, conventional tweezers often require complex electrode arrays and external power sources, have limited charge-generation capabilities, or produce undesirable temperature rises.

The newly proposed self-powered electrostatic tweezer (SET) features a polyvinylidene fluoride trifluoroethylene (P(VDF-TrFE))-based self-powered electrode (SE) that generates large and tunable surface charge density through the triboelectric effect, along with a dielectric substrate that functions as both a tribo-counter material and a supportive platform, and a slippery surface to reduce resistance and biofouling during object manipulation.

Grasping the precise energy landscapes of quantum particles can significantly enhance the accuracy of computer simulations for material sciences. These simulations are instrumental in developing advanced materials for applications in physics, chemistry, and sustainable technologies. The research tackles longstanding questions from the 1980s, paving the way for breakthroughs across various scientific disciplines.

An international group of physicists, led by researchers at Trinity College Dublin, has developed new theorems in quantum mechanics that explain the “energy landscapes” of quantum particle collections. Their work resolves decades-old questions, paving the way for more accurate computer simulations of materials. This advancement could significantly aid scientists in designing materials poised to revolutionize green technologies.

The new theorems have just been published in the prominent journal Physical Review Letters. The results describe how the energy of systems of particles (such as atoms, molecules, and more exotic matter) changes when their magnetism and particle count change. Solving an open problem important to the simulation of matter using computers, this extends a series of landmark works commencing from the early 1980s.

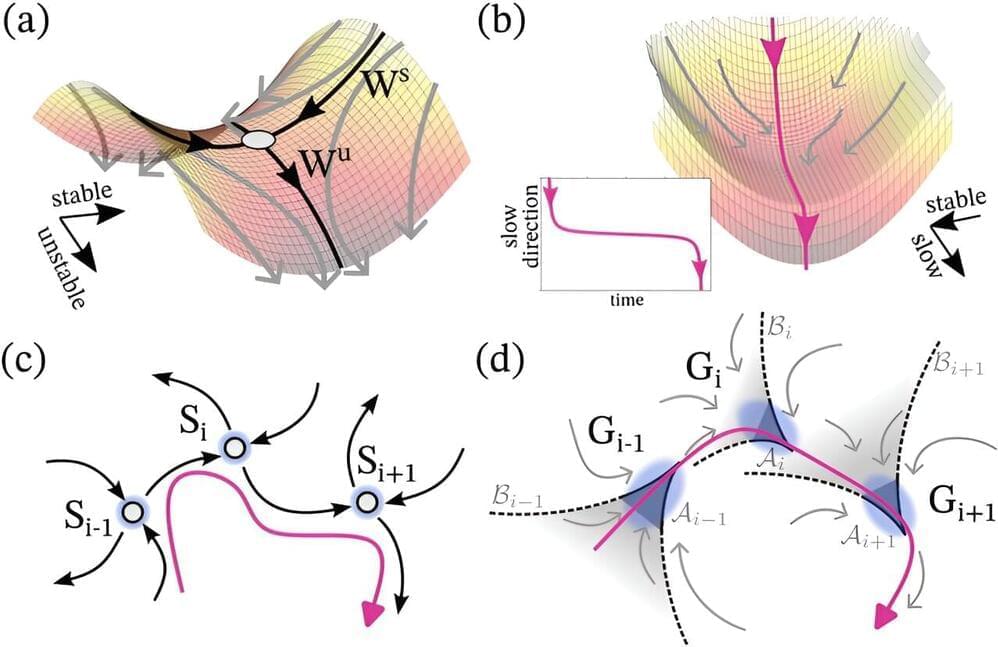

Scientists all over the world use modeling approaches to understand complex natural systems such as climate systems or neuronal or biochemical networks. A team of researchers has now developed a new mathematical framework that explains, for the first time, a mechanism behind long transient behaviors in complex systems.

Wonik manufactures specialty gases and chemicals used by the semiconductor industry. Its clients include Samsung, NXP Semiconductors NV, Infineon Technologies AG and Texas Instruments Inc.

The company signed a joint letter of support with the city of Manor earlier this month, the ABJ reports. Korean company BuildBlock Inc. will be coordinating infrastructure for the project.

For the full report, visit the ABJ website.

The six-wheeled geologist found a fascinating rock that has some indications it may have hosted microbial life billions of years ago, but further research is needed.

A vein-filled rock is catching the eye of the science team of NASA’s Perseverance rover. Nicknamed “Cheyava Falls” by the team, the arrowhead-shaped rock contains fascinating traits that may bear on the question of whether Mars was home to microscopic life in the distant past.

Analysis by instruments aboard the rover indicates the rock possesses qualities that fit the definition of a possible indicator of ancient life. The rock exhibits chemical signatures and structures that could possibly have been formed by life billions of years ago when the area being explored by the rover contained running water. Other explanations for the observed features are being considered by the science team, and future research steps will be required to determine whether ancient life is a valid explanation.

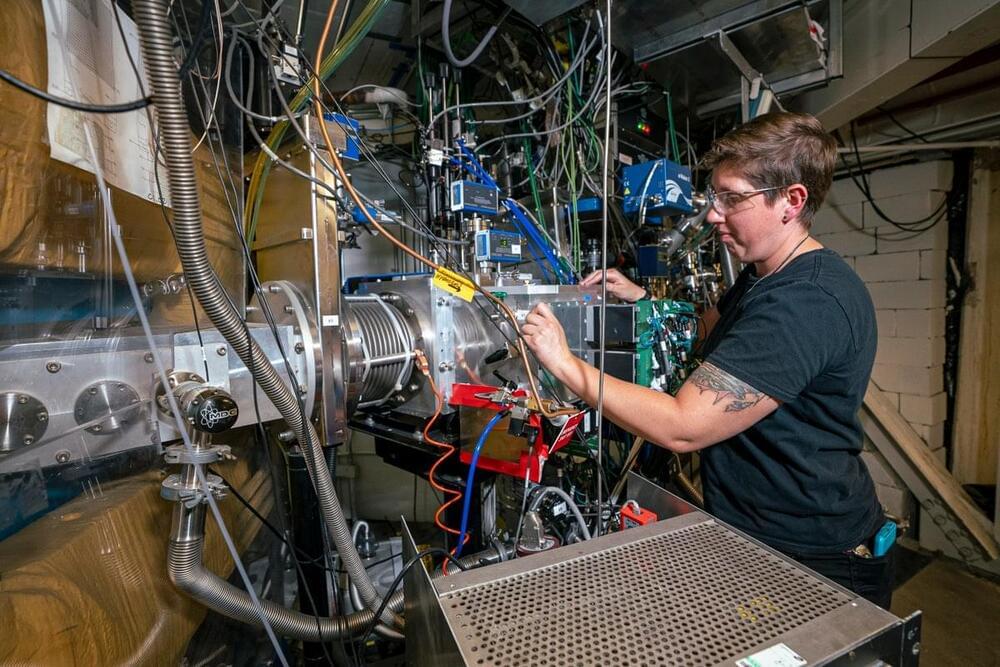

A novel way of making superheavy elements could soon add a new row to the periodic table, allowing scientists to explore uncharted atomic realms.

By Max Springer

A new study by scientists at deCODE Genetics shows that sequence variants drive the correlation between DNA methylation and gene expression. The same variants are linked to various diseases and other human traits.

The research is published in the journal Nature Genetics under the title “The correlation between CpG methylation and gene expression is driven by sequence variants.”

Nanopore sequencing is a new technology developed by ONT (Oxford Nanopore Technology), that enables us to analyze DNA sequences in real-time. With this technology, DNA molecules are drawn through tiny protein pores, and real-time measurements of electric current indicate which nucleotides in the DNA have passed through the pores. This allows the sequence of nucleotides in the DNA to be read, while also making it possible to detect chemical modifications of the nucleotides from these same measurements.

Scientists from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution are seeking a federal permit to experiment in the waters off Cape Cod and see if tweaking the ocean’s chemistry could help slow climate change.

If the project moves forward, it will likely be the first ocean field test of this technology in the U.S. But the plan faces resistance from both environmentalists and the commercial fishing industry.

The scientists want to disperse 6,600 gallons of sodium hydroxide — a strong base — into the ocean about 10 miles south of Martha’s Vineyard. The process, called ocean alkalinity enhancement or OAE, should temporarily increase that patch of water’s ability to absorb carbon dioxide from the air. This first phase of the project, targeted for early fall, will test chemical changes to the seawater, diffusion of the chemical and effects on the ecosystem.