Nov 16, 2022

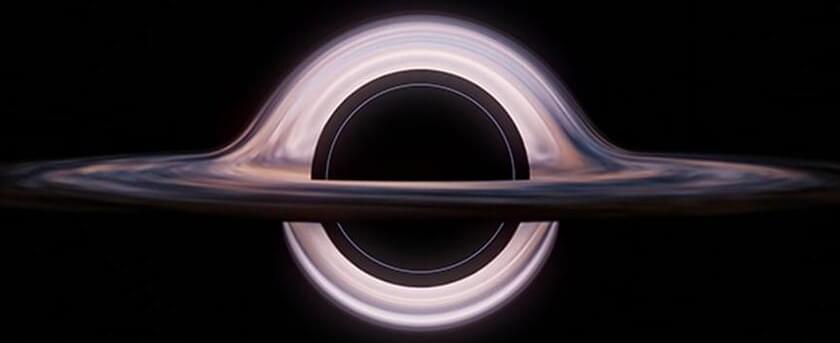

Scientists created a glowing black hole in the lab to test a Stephen Hawking theory

Posted by Gemechu Taye in categories: cosmology, quantum physics

Their experiment could help to create a unified theory of quantum gravity.

A team of physicists from the University of Amsterdam in the Netherlands simulated the event horizon of a black hole in a lab and observed the equivalent of an elusive form of radiation first theorized by Stephen Hawking, a report from Science Alert.

The new discovery could help the scientific community develop a whole new theory that marries the general theory of relativity with the principles of quantum mechanics. John/iStock.