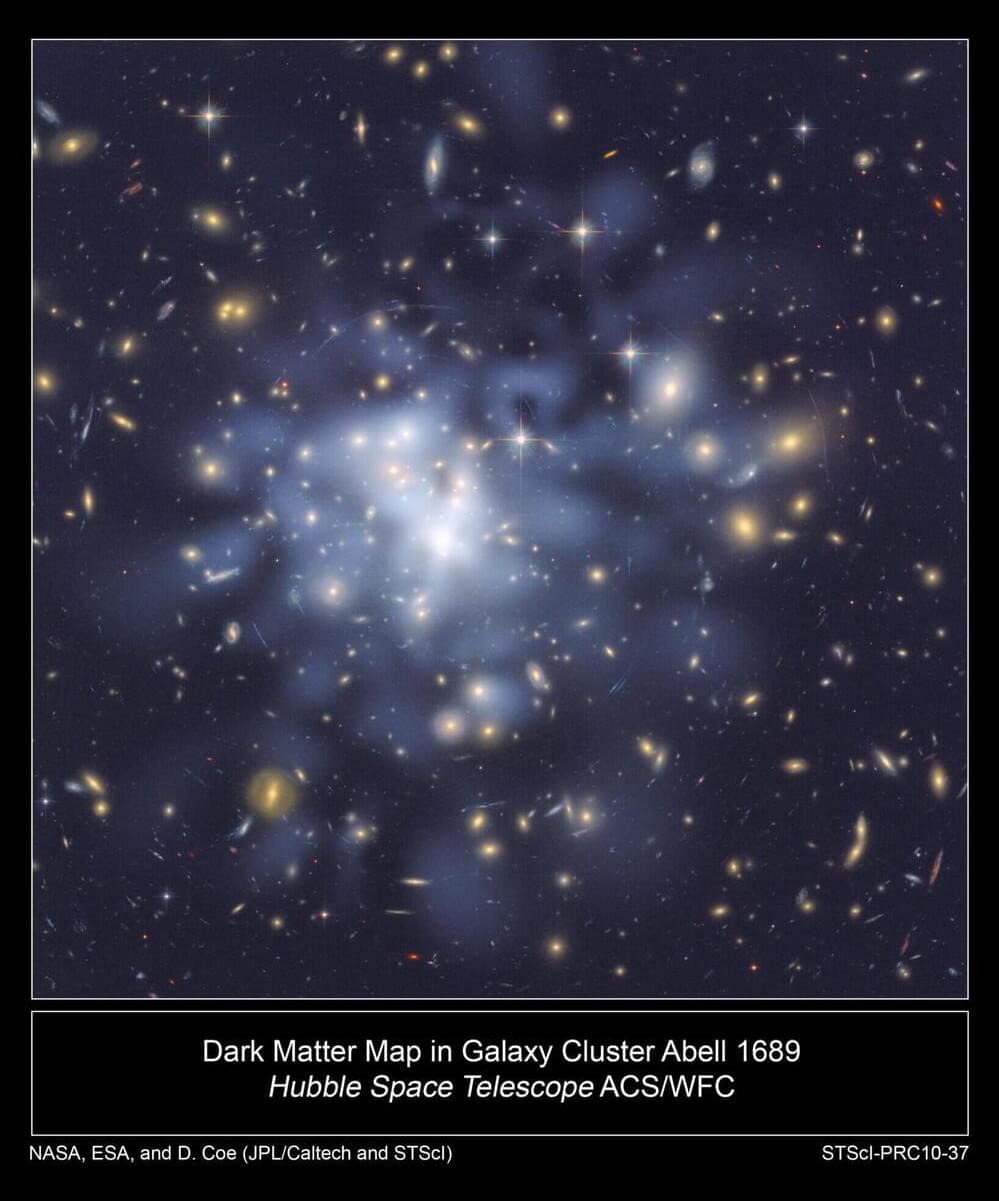

Dark matter remains one of the greatest mysteries of modern physics. It is clear that it must exist, because without dark matter, for example, the motion of galaxies cannot be explained. But it has never been possible to detect dark matter in an experiment.

Currently, there are many proposals for new experiments: They aim to detect dark matter directly via its scattering from the constituents of the atomic nuclei of a detection medium, i.e., protons and neutrons.

A team of researchers—Robert McGehee and Aaron Pierce of the University of Michigan and Gilly Elor of Johannes Gutenberg University of Mainz in Germany—has now proposed a new candidate for dark matter: HYPER, or “HighlY Interactive ParticlE Relics.”