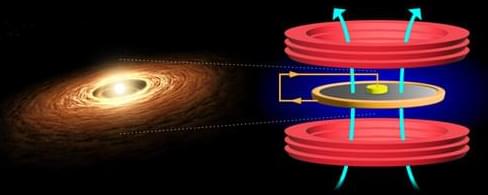

The Migdal effect inside detectors provides a new possibility of probing the sub-GeV dark matter (DM) particles. While there has been well-established methods treating the Migdal effect in isolated atoms, a coherent and complete description of the valence electrons in a semiconductor is still absent. The bremstrahlunglike approach is a promising attempt, but it turns invalid for DM masses below a few tens of MeV. In this paper, we lay out a framework where phonon is chosen as an effective degree of freedom to describe the Migdal effect in semiconductors. In this picture, a valence electron is excited to the conduction state via exchange of a virtual phonon, accompanied by a multiphonon process triggered by an incident DM particle. Under the incoherent approximation, it turns out that this approach can effectively push the sensitivities of the semiconductor targets further down to the MeV DM mass region.