Category: cosmology – Page 384

In the nearby Whirlpool galaxy and its companion galaxy, M51b, two supermassive black holes heat up and devour surrounding material. These two monsters should be the most luminous X-ray sources in sight, but a new study using observations from NASA’s NuSTAR (Nuclear Spectroscopic Telescope Array) mission shows that a much smaller object is competing with the two behemoths.

The most stunning features of the Whirlpool galaxy – officially known as M51a – are the two long, star-filled “arms” curling around the galactic center like ribbons. The much smaller M51b clings like a barnacle to the edge of the Whirlpool. Collectively known as M51, the two galaxies are merging.

At the center of each galaxy is a supermassive black hole millions of times more massive than the Sun. The galactic merger should push huge amounts of gas and dust into those black holes and into orbit around them. In turn, the intense gravity of the black holes should cause that orbiting material to heat up and radiate, forming bright disks around each that can outshine all the stars in their galaxies.

Fermilab plans to send beams of neutrinos and antimatter neutrinos through the earth from Chicago to South Dakota. The DUNE experiment will study neutrino interactions in great detail, with special attention to: 1) comparing the behaviors of neutrinos vs. antineutrinos, 2) looking for proton decay, and 3) searching for the neutrinos emitted by supernovae. The experiment is being built and should start operations in the mid-to-late 2020s.

A new map of the night sky using the Low Frequency Array @LOFAR telescope charts hundreds of thousands of previously unknown galaxies.

The international team behind the unprecedented space survey said their discovery literally shed new light on some of the Universe’s deepest secrets, including the physics of black holes and how clusters of galaxies evolve.

The gravitational pull of a black hole is so strong that nothing, not even light, can escape once it gets too close. However, there is one way to escape a black hole — but only if you’re a subatomic particle.

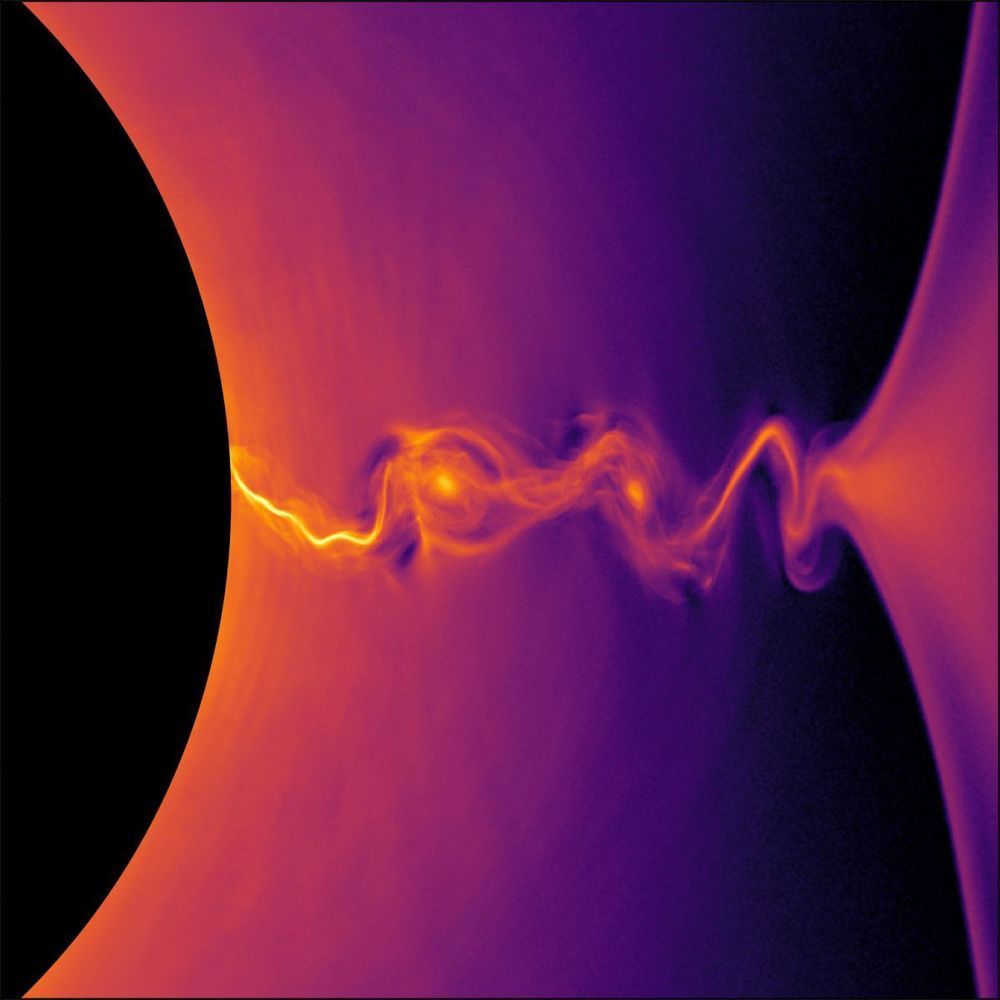

As black holes gobble up the matter in their surroundings, they also spit out powerful jets of hot plasma containing electrons and positrons, the antimatter equivalent of electrons. Just before those lucky incoming particles reach the event horizon, or the point of no return, they begin to accelerate. Moving at close to the speed of light, these particles ricochet off the event horizon and get hurled outward along the black hole’s axis of rotation.

Known as relativistic jets, these enormous and powerful streams of particles emit light that we can see with telescopes. Although astronomers have observed the jets for decades, no one knows exactly how the escaping particles get all that energy. In a new study, researchers with Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (LBNL) in California shed new light on the process. [The Strangest Black Holes in the Universe].

According to most astrophysicists, once you enter a black hole, that’s it for you: gravity will drag you to the singularity — a one-dimensional infinitely small space containing a huge mass — at the speed of light. Then, the black hole will ‘spaghettify you”. Nice.

However, a new study from Berkley University theorises not only that humans could survive going into a black hole, but that their past could be erased, giving way to “infinite futures”.

Physicist Peter Hintz argues that if a human traveller entered a “relatively benign” black hole, they might be able to shed the natural laws of physics — and survive.

However, when astronomers add up all the mass of normal matter in the universe, a third of it can’t be found. (This missing matter is distinct from the still-mysterious dark matter.) However, the matter might be contained in gigantic strands of hot gas in intergalactic space, which are invisible to optical light telescopes. Data from Chandra X-ray Observatory and other telescopes are on the case: https://go.nasa.gov/2N7nWj6

An invisible force is having an effect on our Universe. We can’t see it, and we can’t detect it — but we can observe how it interacts gravitationally with the things we can see and detect, such as light.

Now an international team of astronomers has used one of the world’s most powerful telescopes to analyse that effect across 10 million galaxies in the context of Einstein’s general relativity. The result? The most comprehensive map of dark matter across the history of the Universe to date.

It has yet to complete peer-review, but the map has suggested something unexpected — that dark matter structures might be evolving more slowly than previously predicted.