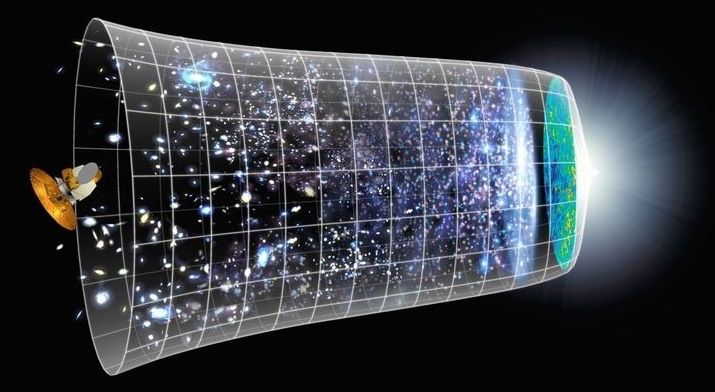

Why does time seem to move forward? It’s a riddle that’s puzzled physicists for well over a century, and they’ve come up with numerous theories to explain time’s arrow. The latest, though, suggests that while time moves forward in our universe, it may run backwards in another, mirror universe that was created on the “other side” of the Big Bang.

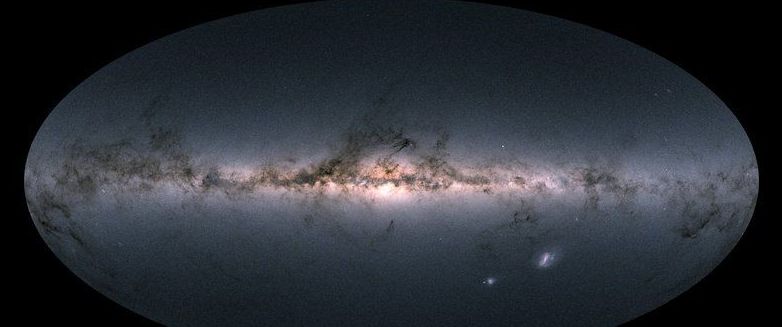

Two leading theories propose to explain the direction of time by way of the relatively uniform conditions of the Big Bang. At the very start, what is now the universe was homogeneously hot, so much so that matter didn’t really exist. It was all just a superheated soup. But as the universe expanded and cooled, stars, galaxies, planets, and other celestial bodies formed, birthing the universe’s irregular structure and raising its entropy.

One theory, proposed in 2004 by Sean Carroll, now a professor at Caltech, and Jennifer Chen, then his graduate student, says that time moves forward because of the contrast in entropy between then and now, with an emphasis on the fact that the future universe will so much more disordered than the past. That movement toward high entropy gives time its direction.