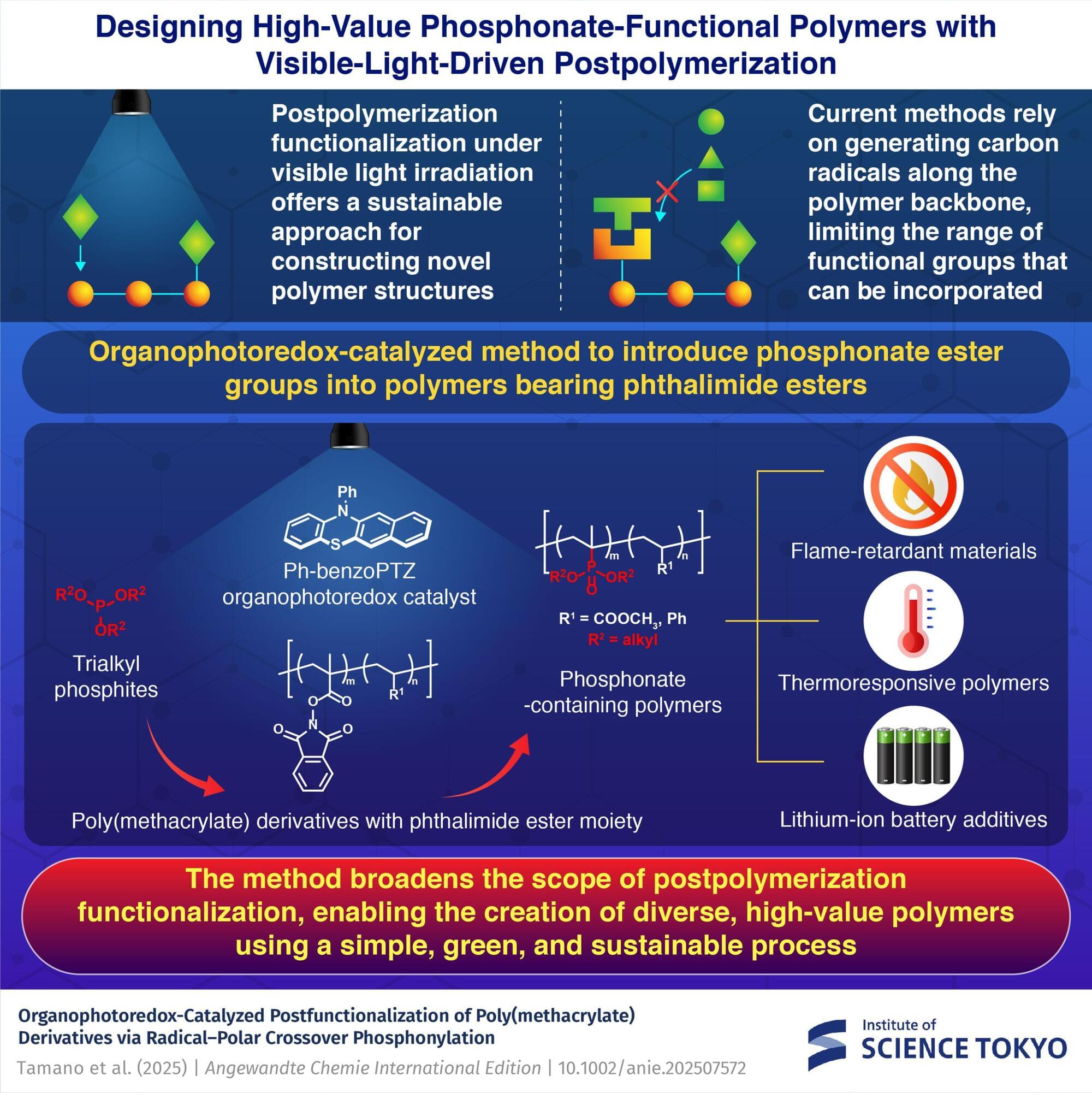

As demand for advanced polymeric materials increases, post-functionalization has emerged as an effective strategy for designing functional polymers. This approach involves modifying existing polymer chains by introducing new chemical groups after their synthesis, allowing for the transformation of readily available polymers into materials with desirable properties.

Postfunctionalization can be performed under mild conditions using visible light in the presence of catalysts, which provides a sustainable route for developing high-value polymers. However, existing methods often rely on generating carbon radicals along the polymer chain, limiting the variety of functional groups that can be introduced.

In a significant advancement, a team led by Professor Shinsuke Inagi from the Department of Chemical Science and Engineering, School of Materials and Chemical Technology at Institute of Science Tokyo (Science Tokyo), Japan, has developed a postfunctionalization technique that allows for the incorporation of phosphonate esters under visible light conditions. This breakthrough paves the way for a broader range of polymer modifications.