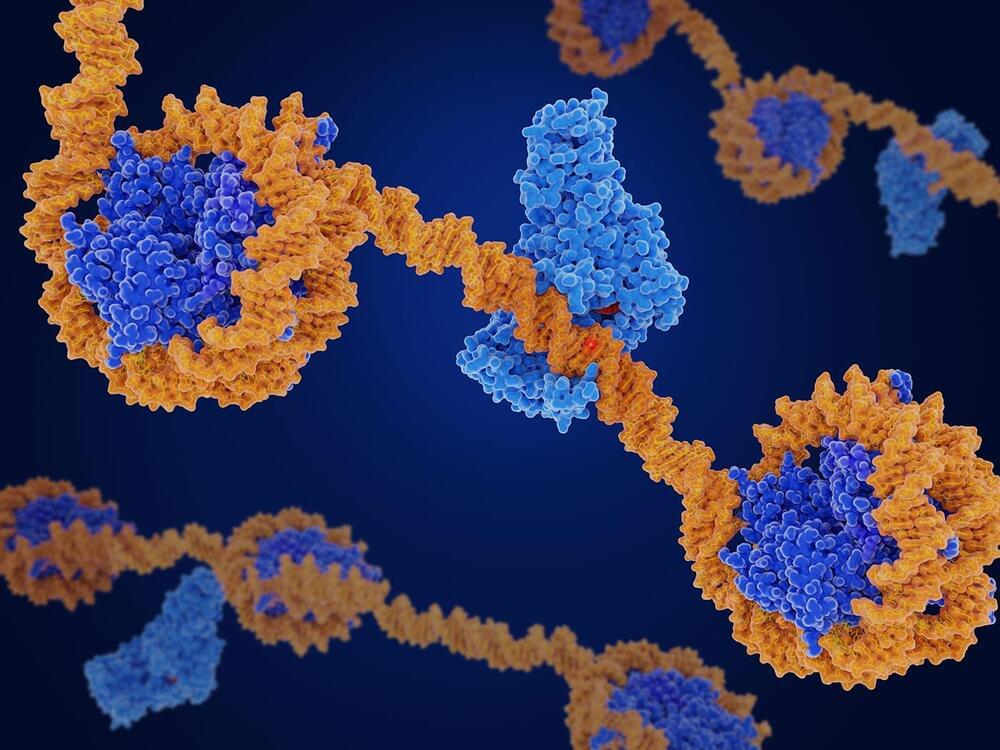

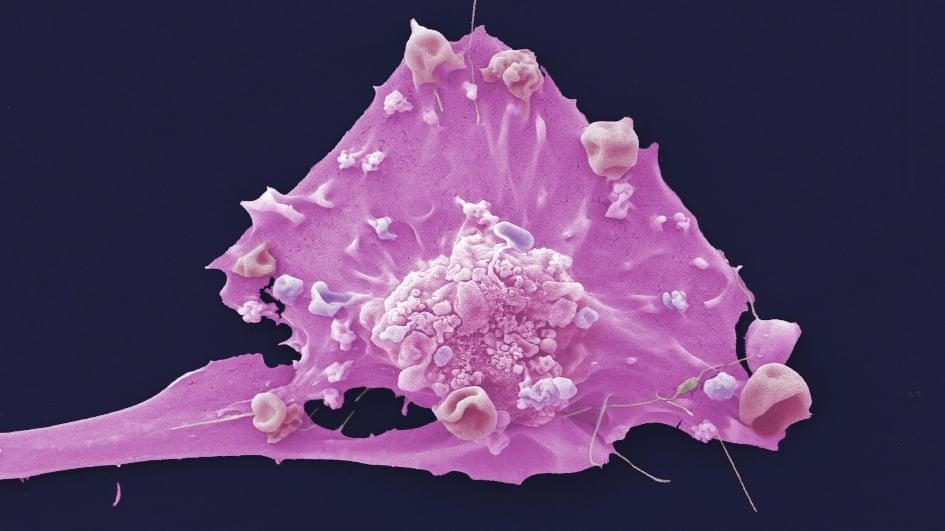

Large-scale protein and gene profiling have massively expanded the landscape of cancer-associated proteins and gene mutations, but it has been difficult to discern whether they play an active role in the disease or are innocent bystanders. In a study published in Nature Cancer, researchers at Baylor College of Medicine revealed a powerful and unbiased machine learning-based approach called FunMap for assessing the role of cancer-associated mutations and understudied proteins, with broad implications for advancing cancer biology and informing therapeutic strategies.

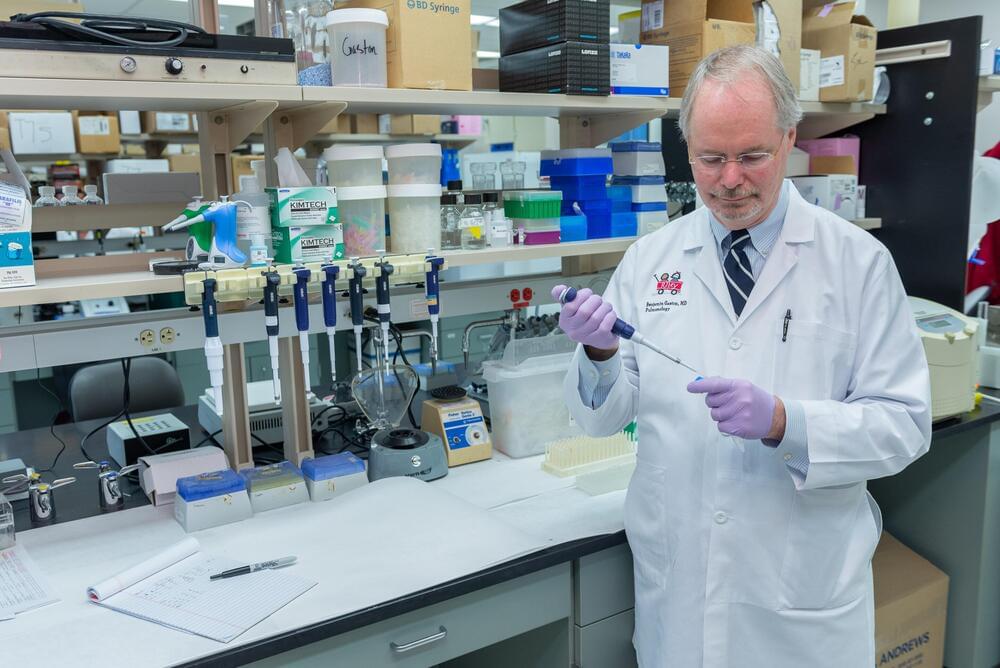

“Gaining functional information on the genes and proteins associated with cancer is an important step toward better understanding the disease and identifying potential therapeutic targets,” said corresponding author Dr. Bing Zhang, professor of molecular and human genetics and part of the Lester and Sue Smith Breast Center at Baylor.

“Our approach to gain functional insights into these genes and proteins involved using machine learning to develop a network mapping their functional relationships,” said Zhang, member of Baylor’s Dan L Duncan Comprehensive Cancer Center and a McNair Scholar. “It’s like, I may not know anything about you, but if I know your LinkedIn connections, I can infer what you do.”