Feb 7, 2024

Team discovers mechanism that protects tissue after faulty gene expression

Posted by Paul Battista in categories: biotech/medical, genetics, life extension

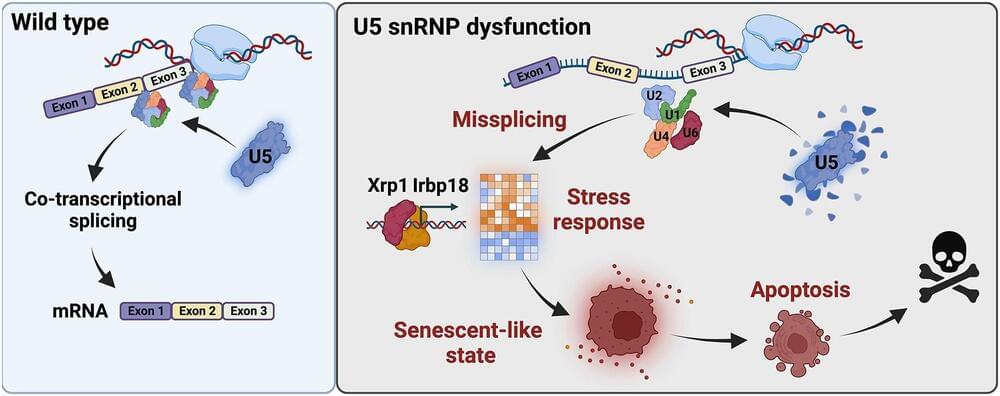

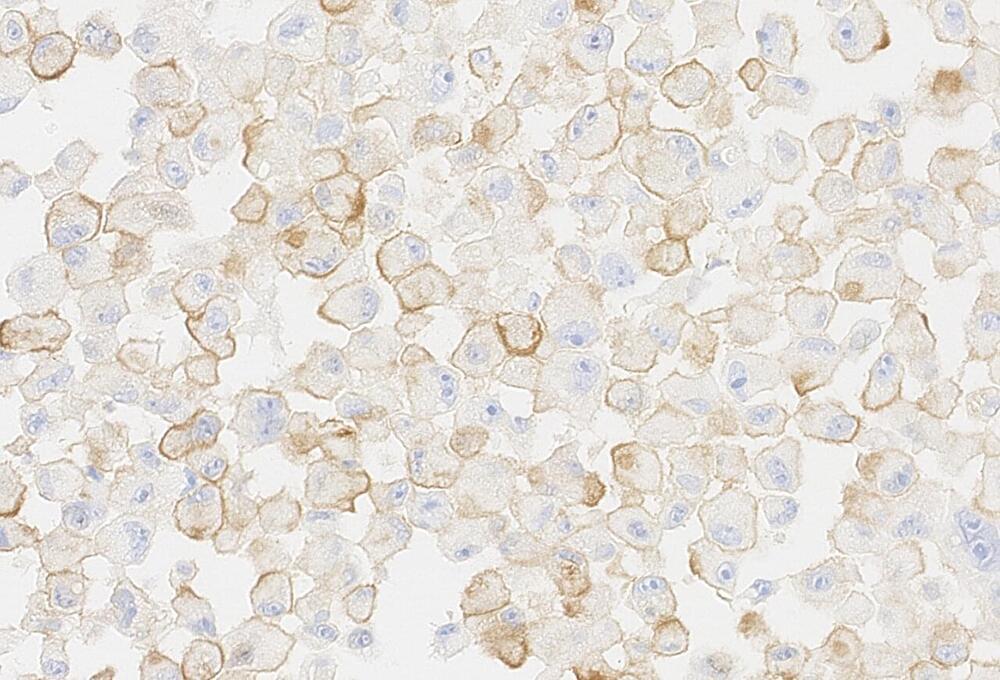

A study at the University of Cologne’s CECAD Cluster of Excellence in Aging Research has identified a protein complex that is activated by defects in the spliceosome, the molecular scissors that process genetic information. Future research could lead to new therapeutic approaches to treat diseases caused by faulty splicing.

The genetic material, in the form of DNA, contains the information that is crucial for the correct functioning of every human and animal cell. From this information repository, RNA, an intermediate between DNA and protein, the functional unit of the cell, is generated. During this process, the genetic information must be tailored for specific cell functions. Information that is not needed (introns) is cut out of the RNA and the important components for proteins (exons) are preserved.

A team of researchers led by Professor Dr. Mirka Uhlirova at the University of Cologne’s CECAD Cluster of Excellence in Aging Research has now discovered that if the processing of this information no longer works properly, a protein complex (C/EBP heterodimer) is activated and directs the cell towards a dormant state, known as cellular senescence. The results appear under the title “Xrp1 governs the stress response program to spliceosome dysfunction” in Nucleic Acids Research.