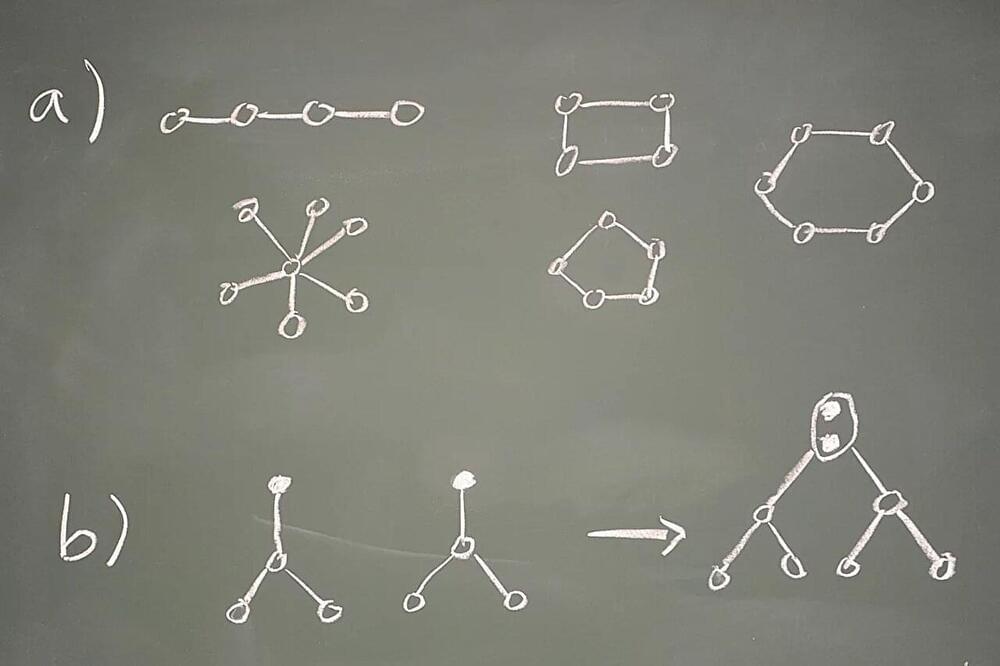

The entanglement of quantum systems is the foundation of all quantum information technologies. Complex forms of entanglement between several quantum bits are particularly interesting.

Category: quantum physics – Page 213

Researchers at the University of Rochester have used surface acoustic waves to overcome a significant obstacle in the quest to realize a quantum internet.

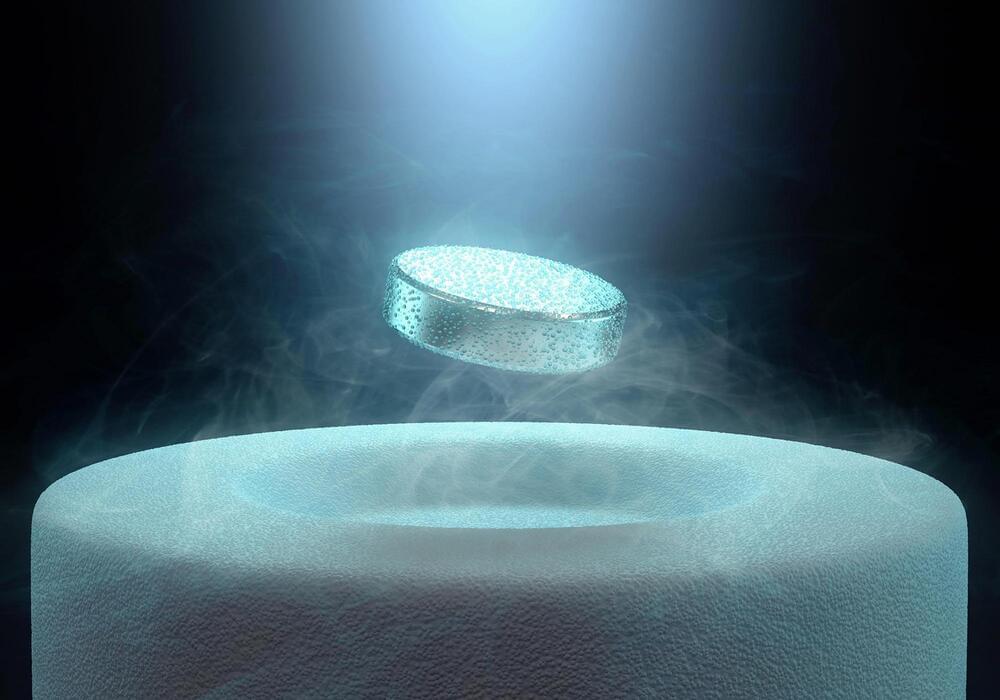

Flatiron Institute senior research scientist Shiwei Zhang and his team have utilized the Hubbard model to computationally re-create key features of the superconductivity in materials called cuprates that have puzzled scientists for decades.

Superfast hovering trains, long-distance power transmission without energy loss, and quicker MRI scanners — all these incredible technological innovations could be within reach if we could develop a material that conducts electricity without any resistance, or “superconducts,” at approximately room temperature.

In a paper recently published in the journal Science, researchers report a breakthrough in our understanding of the origins of superconductivity at relatively high (though still frigid) temperatures. The findings concern a class of superconductors that has puzzled scientists since 1986, called ‘cuprates.’

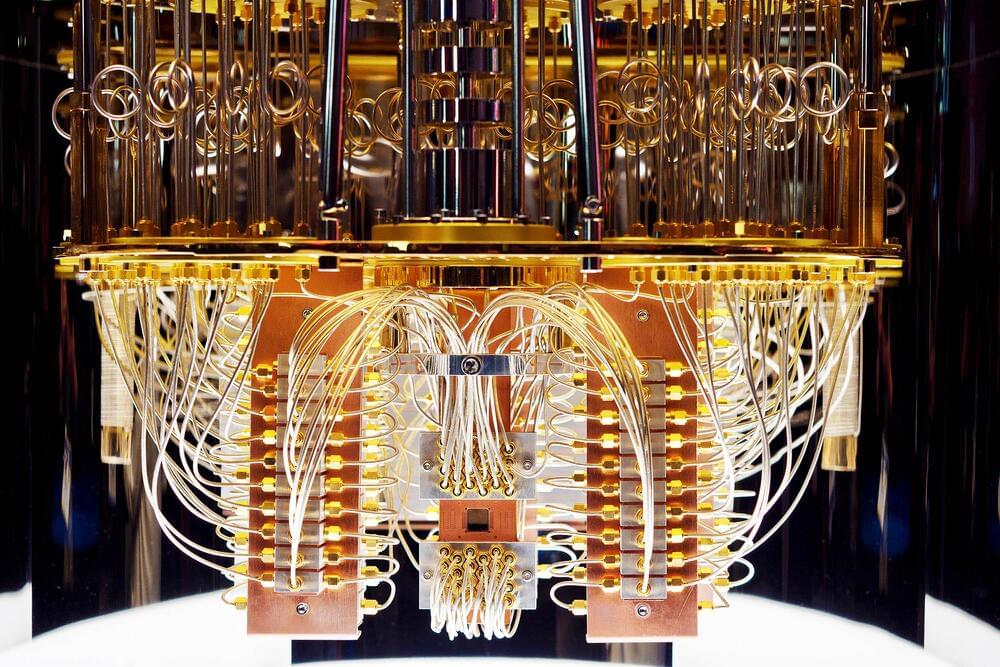

It’s mind-bending tech that could soon transform our lives. What do qubits and cats have to do with it?

Scientists have produced an enhanced, ultra-pure form of silicon that allows the construction of high-performance qubit devices. This fundamental component is crucial for paving the way towards scalable quantum computing.

The finding, published in the journal Communications Materials – Nature, could define and push forward the future of quantum computing.

The research was led by Professor Richard Curry from the Advanced Electronic Materials group at The University of Manchester, in collaboration with the University of Melbourne in Australia.

Silicon spin qubits are promising for the realisation of scalable quantum computing platforms but their coherence times in natural silicon are limited by the non-zero nuclear spin of the 29Si isotope. Here, enriched 28 Si down to 2.3 ppm residual 29Si is obtained by focused ion beam implantation.

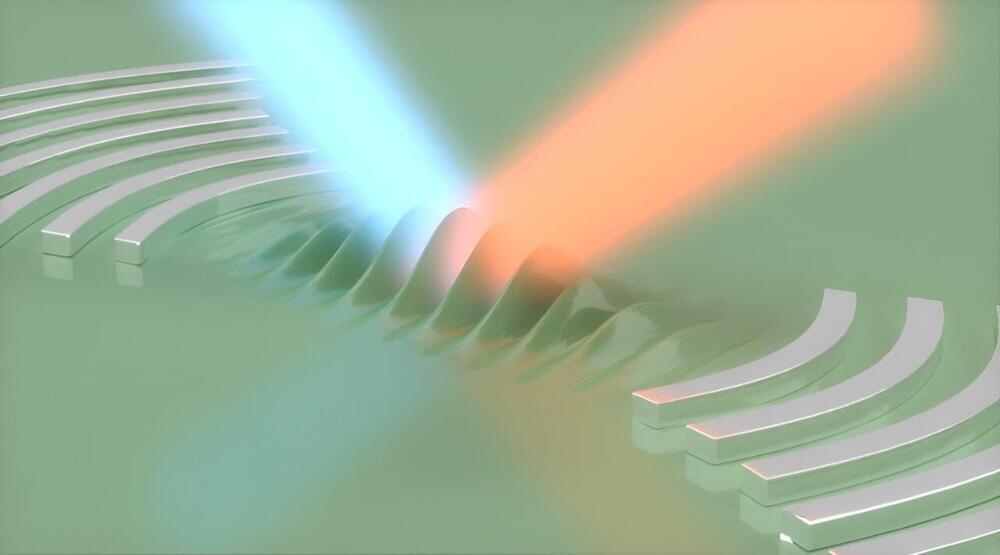

An international collaboration of researchers, led by Philip Walther at University of Vienna, have achieved a significant breakthrough in quantum technology, with the successful demonstration of quantum interference among several single photons using a novel resource-efficient platform. The work published in the journal Science Advances represents a notable advancement in optical quantum computing that paves the way for more scalable quantum technologies.

Interference among photons, a fundamental phenomenon in quantum optics, serves as a cornerstone of optical quantum computing.

It involves harnessing the properties of light, such as its wave-particle duality, to induce interference patterns, enabling the encoding and processing of quantum information.

Start speaking a new language in 3 weeks with Babbel 🎉. Get up to 60% OFF your subscription ➡Here: https://bit.ly/sabinebabbel05

When Roger Penrose originally came out with the idea that the human brain uses quantum effects in microtubules and that was the origin of consciousness, many thought the idea was a little crazy. According to a new study, it turns out that Penrose was actually right… about the microtubules anyways. Let’s have a look.

Paper: https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs…

🤓 Check out my new quiz app ➜ http://quizwithit.com/

💌 Support me on Donorbox ➜ https://donorbox.org/swtg.

📝 Transcripts and written news on Substack ➜ https://sciencewtg.substack.com/

👉 Transcript with links to references on Patreon ➜ / sabine.

📩 Free weekly science newsletter ➜ https://sabinehossenfelder.com/newsle…

👂 Audio only podcast ➜ https://open.spotify.com/show/0MkNfXl…

🔗 Join this channel to get access to perks ➜

/ @sabinehossenfelder.

🖼️ On instagram ➜ / sciencewtg.

#science #sciencenews #quantum #biology

In a recent study merging the fields of quantum physics and computer science, Dr. Jun-Jie Zhang and Prof. Deyu Meng have explored the vulnerabilities of neural networks through the lens of the uncertainty principle in physics. Their work, published in the National Science Review, draws a parallel between the susceptibility of neural networks to targeted attacks and the limitations imposed by the uncertainty principle—a well-established theory in quantum physics that highlights the challenges of measuring certain pairs of properties simultaneously.

The researchers’ quantum-inspired analysis of neural network vulnerabilities suggests that adversarial attacks leverage the trade-off between the precision of input features and their computed gradients. “When considering the architecture of deep neural networks, which involve a loss function for learning, we can always define a conjugate variable for the inputs by determining the gradient of the loss function with respect to those inputs,” stated in the paper by Dr. Jun-Jie Zhang, whose expertise lies in mathematical physics.

This research is hopeful to prompt a reevaluation of the assumed robustness of neural networks and encourage a deeper comprehension of their limitations. By subjecting a neural network model to adversarial attacks, Dr. Zhang and Prof. Meng observed a compromise between the model’s accuracy and its resilience.

BASEL, Switzerland — A reliable and ultra-powerful quantum computer could finally be on the horizon. Researchers from the University of Basel and the NCCR SPIN in Switzerland have made an exciting advancement in the world of quantum computing, achieving the first controllable interaction between two “hole spin qubits” inside a standard silicon transistor. This leap forward could eventually allow quantum computer chips to carry millions of qubits — a feat that would drastically scale up their processing power and potentially replace the modern computer.

First, we need to explain some of the high-tech terms involved in the new study published in Nature Physics. A qubit is the quantum equivalent of a bit, the fundamental building block of data in conventional computing. While a standard bit can be either a 0 or a 1, qubits can be both simultaneously, thanks to the principles of quantum mechanics. This allows quantum computers to handle complex calculations at speeds today’s standard computers will never achieve.

The concept of hole spin qubits might sound even more abstract. In simple terms, in the materials used for making computer chips, electrons (tiny particles with negative charge) move around, and sometimes they leave behind empty spaces or “holes.”