Pablo viñas martínez, esperanza lópez, and alejandro bermudez.

Instituto de Física Teórica, UAM-CSIC, Universidad Autónoma de Madrid, Cantoblanco, 28,049 Madrid, Spain.

Get full text pdfRead on arXiv VanityComment on Fermat’s library.

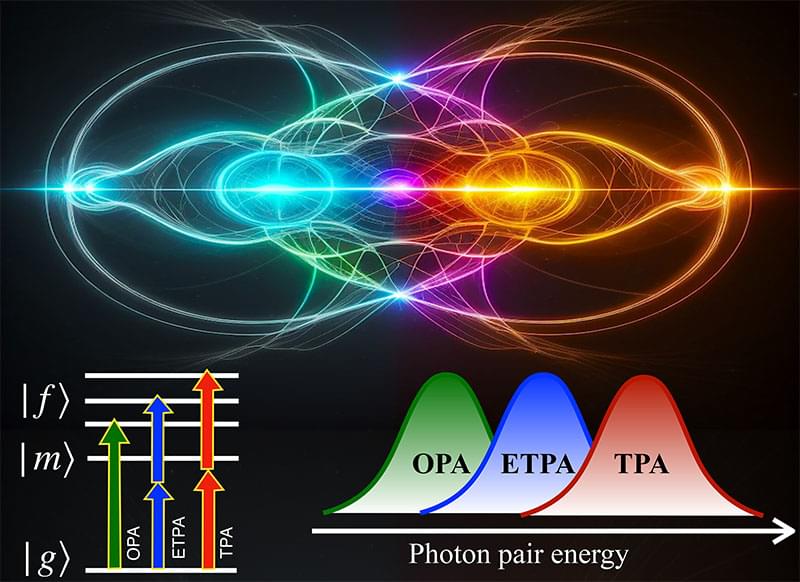

Researchers at the University of Michigan have found a way to examine tiny structures, such as bacteria and genes, with reduced damage compared to traditional light sources.

The new technique involves spectroscopy, which is the study of how matter absorbs and emits light and other forms of radiation, and it takes advantage of quantum mechanics to study the structure and dynamics of molecules in ways that are not possible using conventional light sources.

“This research examined a quantum light spectroscopy technique called entangled two-photon absorption (ETPA) that takes advantage of entanglement to reveal the structures of molecules and how ETPA acts at ultrafast speeds to determine properties that cannot be seen with classical spectroscopy,” said study senior author Theodore Goodson, U-M professor of chemistry and of macromolecular science and engineering.

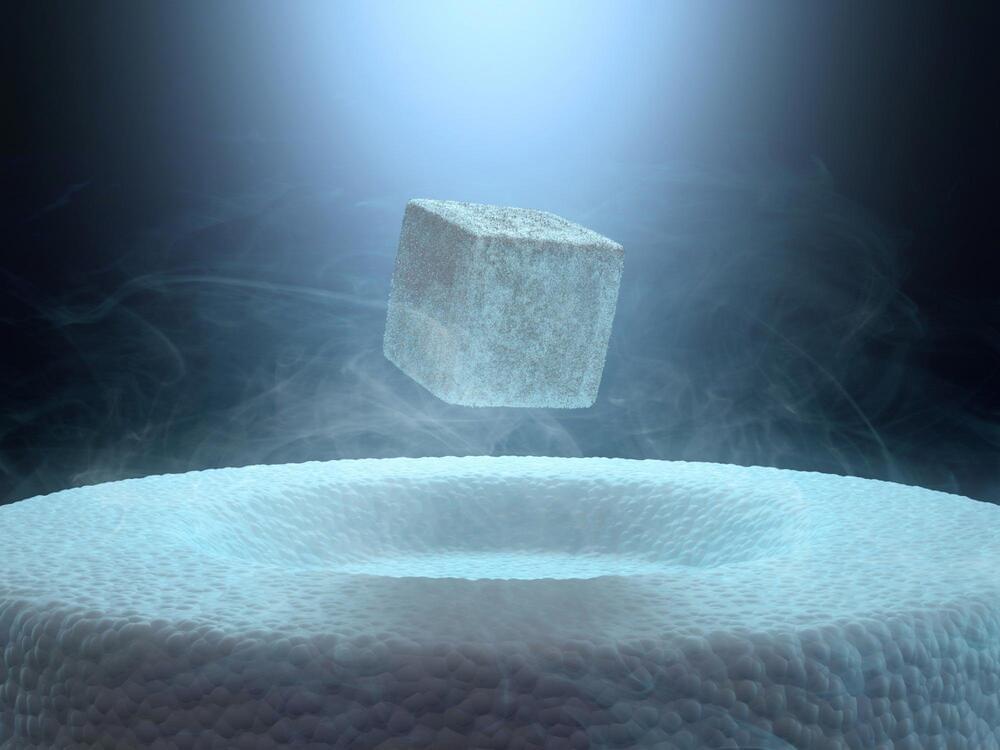

A new paper explores the quantum Griffith singularity in phase transitions, focusing on recent studies that could expand our understanding of high-temperature superconductivity in unconventional materials.

Exploring exotic quantum phase transitions has long been a key focus in condensed matter physics. A critical phenomenon in a phase transition is determined entirely by its universality class, which is governed by spatial and/or order parameters and remains independent of microscopic details. Quantum phase transitions, a subset of phase transitions, occur due to quantum fluctuations and are tuned by specific system parameters at the zero-temperature limit.

The superconductor-insulator/metal phase transition is a classic example of quantum phase transition, which has been intensely studied for more than 40 years. Disorder is considered one of the most important influencing factors, and therefore has received widespread attention. During the phase transitions, the system usually satisfies scaling invariance, so the universality class will be characterized by a single critical exponent. In contrast, the peculiarity of quantum Griffith singularity is that it breaks the traditional scaling invariance, where exotic physics emerges.

At the very smallest scales, our intuitive view of reality no longer applies. It’s almost as if physics is fundamentally indecisive, a truth that gets harder to ignore as we zoom in on the particles that pixelate our Univerrse.

In order to better understand it, physicists had to devise an entirely new framework to place it in, one based on probability over certainty. This is quantum theory, and it describes all sorts of phenomena, from entanglement to superposition.

Yet in spite of a century of experiments showing just how useful quantum theory is at explaining what we see, it’s hard to shake our ‘classical’ view of the Universe’s building blocks as reliable fixtures in time and space. Even Einstein was forced to ask his fellow physicist, “Do you really believe the Moon is not there when you are not looking at it?”

Gov. J.B. Pritzker on Tuesday plans to announce a major partnership with the U.S. Department of Defense’s research and development agency to further expand quantum research in Illinois.

The Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, or DARPA, will take residency on the state’s quantum campus to establish a program where quantum computing prototypes will be tested. The location of the campus is expected to be announced soon.

According to DARPA, the goal of the “Quantum Benchmarking Initaitive,” or QBI, will be to evaluate and test quantum computing claims and “separate hype from reality.”

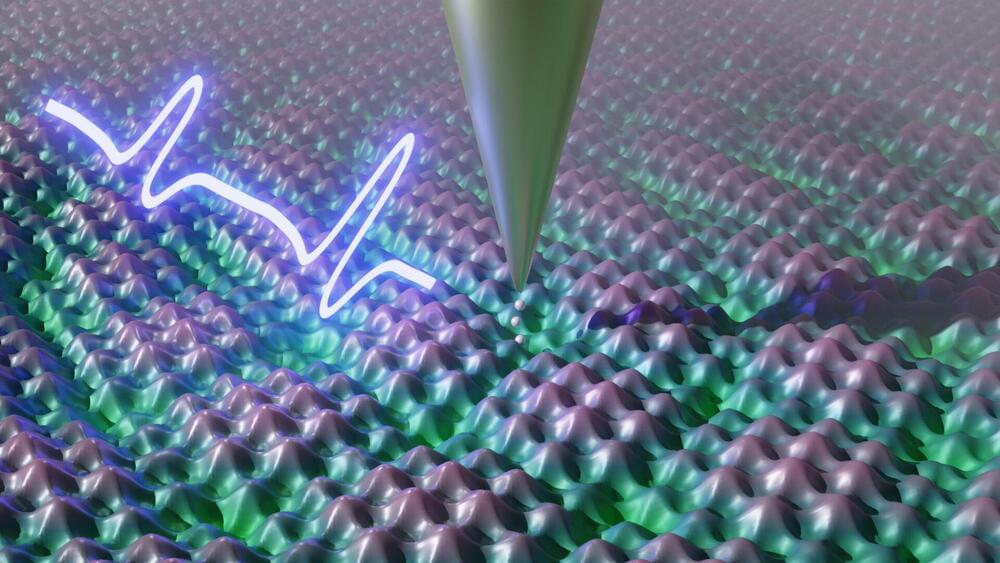

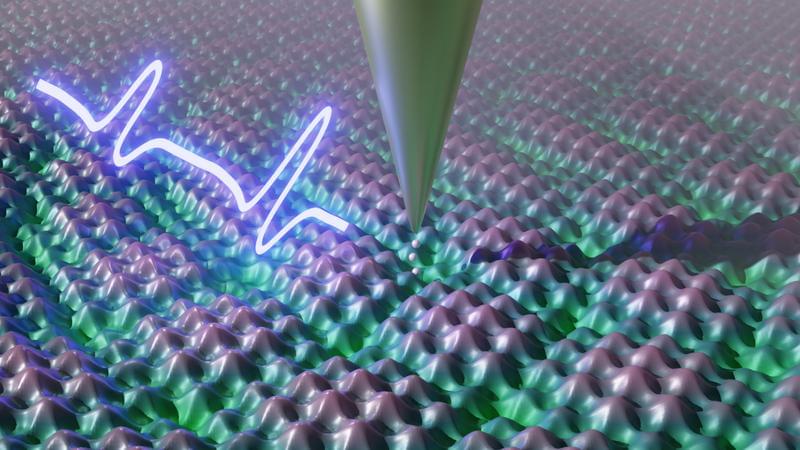

Physicists at the University of Stuttgart under the leadership of Prof. Sebastian Loth are developing quantum microscopy which enables them for the first time to record the movement of electrons at the atomic level with both extremely high spatial and temporal resolution. Their method has the potential to enable scientists to develop materials in a much more targeted way than before.

The researchers have published their findings in the journal Nature Physics (“Terahertz spectroscopy of collective charge density wave dynamics at the atomic scale”).

“With the method we developed, we can make things visible that no one has seen before,” says Prof. Sebastian Loth, Managing Director of the Institute for Functional Matter and Quantum Technologies (FMQ) at the University of Stuttgart. “This makes it possible to settle questions about the movement of electrons in solids that have been unanswered since the 1980s.” However, the findings of Loth’s group are also of very practical significance for the development of new materials.

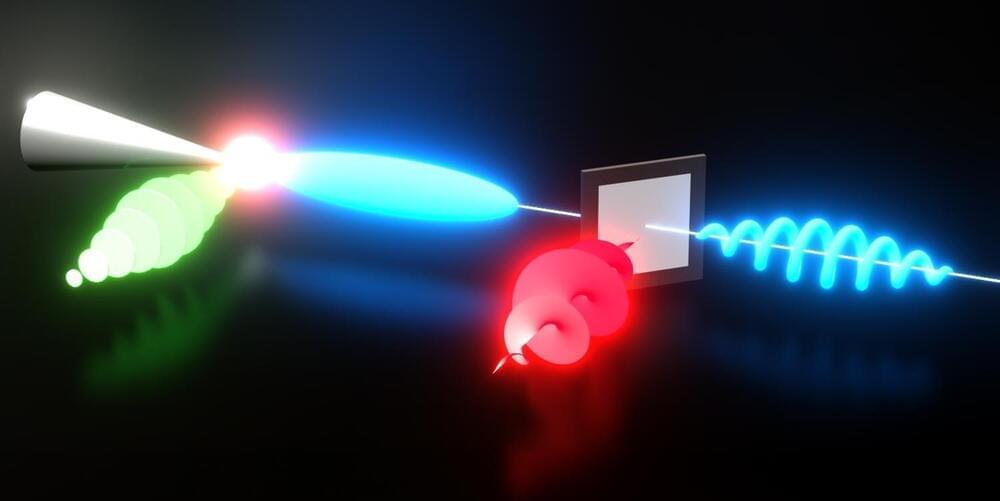

Physicists at the University of Konstanz have discovered a way to imprint a previously unseen geometrical form of chirality onto electrons using laser light, creating chiral coils of mass and charge.

This breakthrough in manipulating electron chirality has vast implications for quantum optics, particle physics, and electron microscopy, paving the way for new scientific explorations and technological innovations.

Understanding Chirality and Its Implications.

Dive into the world of tachyons, the elusive particles that might travel faster than light and hold the key to understanding dark matter and the universe’s expansion. Join us as we explore groundbreaking research that challenges our deepest physics laws and hints at a universe far stranger than we ever imagined. Don’t miss out on this thrilling cosmic journey!

Chapters:

00:00 Introduction.

00:39 Racing Beyond Light.

03:26 The Tachyon Universe Model.

05:57 Beyond Cosmology: Tachyons’ Broader Impact.

08:31 Outro.

08:44 Enjoy.

Visit our website for up-to-the-minute updates:

www.nasaspacenews.com.

Follow us.

Facebook: / nasaspacenews.

Twitter: / spacenewsnasa.

Join this channel to get access to these perks:

/ @nasaspacenewsagency.

#NSN #NASA #Astronomy#tachyons #fasterthanlight #darkmatter #universesecrets #cosmicacceleration #theoreticalphysics #Einsteintheory #supernovae #spacemysteries #cosmology #particlephysics #lightspeed #universeexpansion #sciencebreakthroughs #physicsexplained #futuretechnologies #spaceexploration #cosmos #astrophysics #modernphysics #sciencerevolution #relativitytheory #speedoflight #spacetime #universetheory #quantumphysics #energyphysics #newscience #cosmicphenomena #physicsresearch