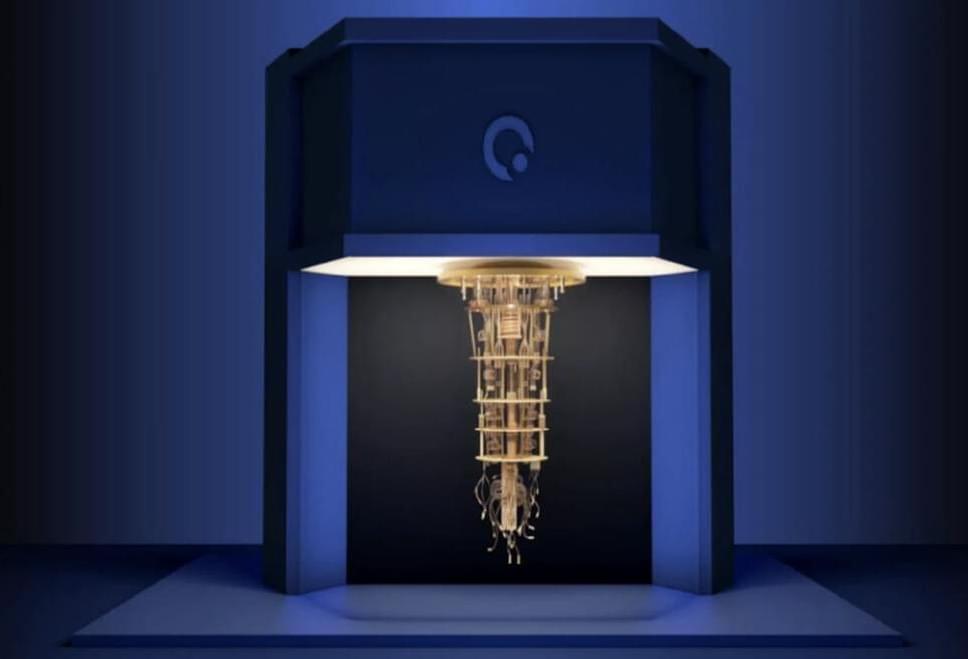

The third-generation superconducting quantum computer, “Origin Wukong,” was launched on January 6 at Origin Quantum Computing Technology in Hefei, according to Chinese-based media outlet, The Global Times, as reported by the Pakistan Today.

According to the news outlets, the “Origin Wukong” is powered by a 72-qubit superconducting quantum chip, known as the “Wukong chip.” This development marks a new milestone in China’s quantum computing journey as it’s the most advanced programmable and deliverable superconducting quantum computer in China, as per a joint statement from the Anhui Quantum Computing Engineering Research Center and the Anhui Provincial Key Laboratory of Quantum Computing Chips, shared with the Global Times.

Superconducting quantum computers, such as the “Origin Wukong,” rely on a approach being investigated by several other quantum computer makers, including IBM and Google quantum devices.