A first-principles model accounts for the wide range of critical temperatures (Tc’s) for four materials and suggests a parameter that determines Tc in any high-temperature superconductor.

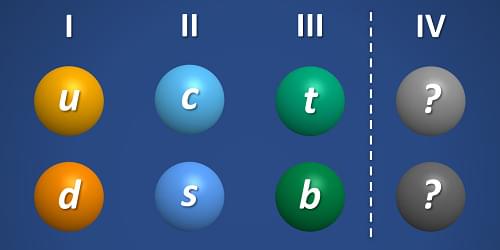

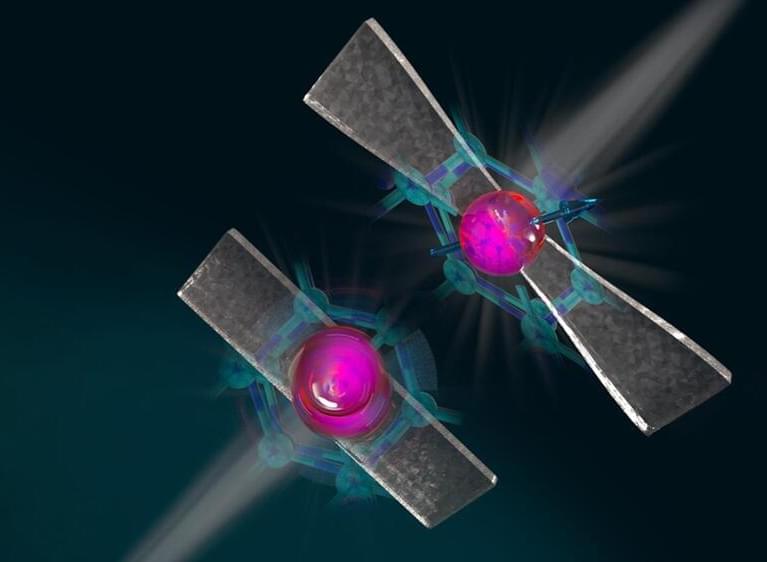

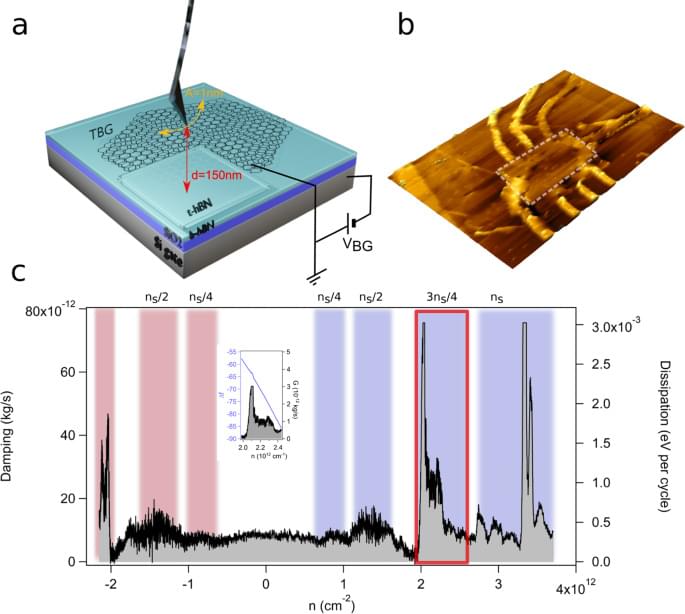

Since the first high-temperature superconducting materials, known as the cuprates, were discovered in 1986, researchers have struggled to explain their properties and to find materials with even higher superconducting transition temperatures (Tc’s). One puzzle has been the cuprates’ wide variation in Tc, ranging from below 10 K to above 130 K. Now Masatoshi Imada of Waseda University in Japan and his colleagues have used first-principles calculations to determine the order parameters—which measure the density of superconducting electrons—for four cuprate materials and have predicted the Tc’s based on those order parameters [1]. The researchers have also found what they believe is the fundamental parameter that determines Tc in a given material, which they hope will lead to the development of higher-temperature superconductors.

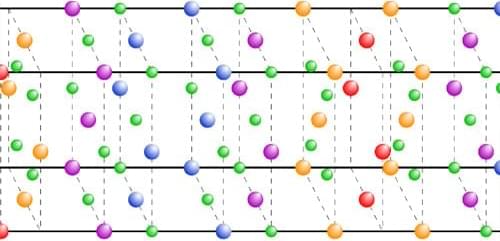

For each material, Imada and his colleagues applied the basic principles of quantum mechanics, focusing on the planes of copper and oxygen atoms that are known to host the superconducting electrons. They used a combination of numerical techniques, including one supplemented by machine learning, and did not require any adjustable parameters.