A team of researchers used quantum computing and computer learning to describe what is believed to be the interior of a black hole.

Category: quantum physics – Page 389

‘Spin’ is a fundamental quality of fundamental particles like the electron, invoking images of a tiny sphere revolving rapidly on its axis like a planet in a shrunken solar system.

Only it isn’t. It can’t. For one thing, electrons aren’t spheres of matter but points described by the mathematics of probability.

But California Institute of Technology philosopher of physics Charles T. Sebens argues such a particle-based approach to one of the most accurate theories in physics might be misleading us.

Circa 2013 face_with_colon_three

A ten-dimensional theory of gravity makes the same predictions as standard quantum physics in fewer dimensions.

Edited by Rob Appleby and Connie Potter (Comma Press)

IN The Ogre, the Monk and the Maiden, Margaret Drabble’s ingenious story for the new sci-fi anthology Collision, a character called Jaz works on “the interface of language and quantum physics”. Jaz’s speciality is “the speaking of the inexpressible”. Science fiction authors have long grappled with translating cutting-edge research – much of it grounded in what Drabble calls “the Esperanto of Equations” – into everyday language and engaging plots.

Sean Carroll CalTech, John’s Hopkins, Santa Fe Institute One of the great intellectual achievements of the twentieth century was the theory of quantum mech…

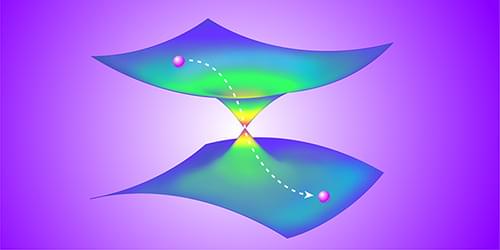

A quantum device shows promise for simulating molecular dynamics in a difficult-to-model photochemical process that is relevant to vision.

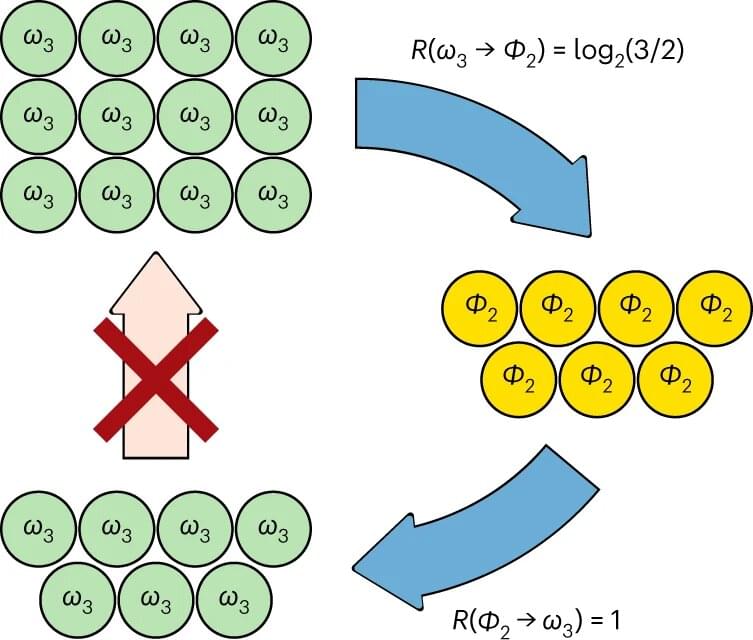

The second law of thermodynamics is often considered to be one of only a few physical laws that is absolutely and unquestionably true. The law states that the amount of ‘entropy’—a physical property—of any closed system can never decrease. It adds an ‘arrow of time’ to everyday occurrences, determining which processes are reversible and which are not. It explains why an ice cube placed on a hot stove will always melt, and why compressed gas will always fly out of its container (and never back in) when a valve is opened to the atmosphere.

Only states of equal entropy and energy can be reversibly converted from one to the other. This reversibility condition led to the discovery of thermodynamic processes such as the (idealized) Carnot cycle, which poses an upper limit to how efficiently one can convert heat into work, or the other way around, by cycling a closed system through different temperatures and pressures. Our understanding of this process underpinned the rapid economic development during the Western Industrial Revolution.

The beauty of the second law of thermodynamics is its applicability to any macroscopic system, regardless of the microscopic details. In quantum systems, one of these details may be entanglement: a quantum connection that makes separated components of the system share properties. Intriguingly, quantum entanglement shares many profound similarities with thermodynamics, even though quantum systems are mostly studied in the microscopic regime.

In recent years, many physicists and computer scientists have been working on the development of quantum computing technologies. These technologies are based on qubits, the basic units of quantum information.

In contrast with classical bits, which have a value of 0 or 1, qubits can exist in superposition states, so they can have a value of 0 and 1 simultaneously. Qubits can be made of different physical systems, including electrons, nuclear spins (i.e., the spin state of a nucleus), photons, and superconducting circuits.

Electron spins confined in silicon quantum dots (i.e., tiny silicon-based structures) have shown particular promise as qubits, particularly due to their long coherence times, high gate fidelities and compatibility with existing semiconductor manufacturing methods. Coherently controlling multiple electron spin states, however, can be challenging.

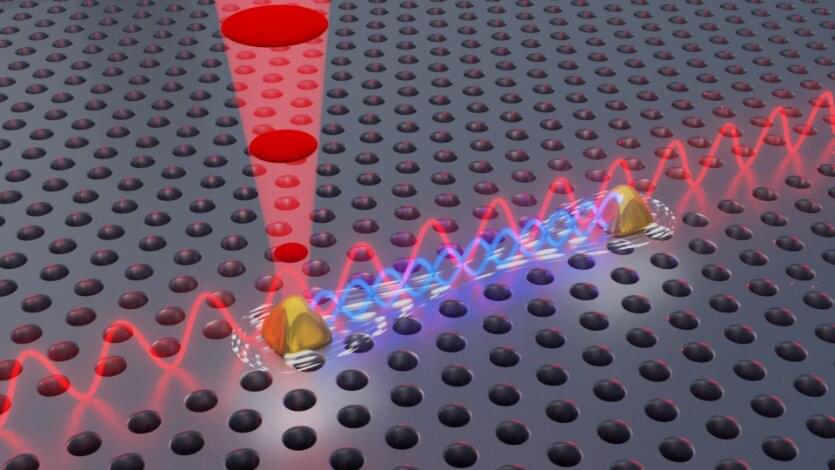

In a new breakthrough, researchers at the University of Copenhagen, in collaboration with Ruhr University Bochum, have solved a problem that has caused quantum researchers headaches for years. The researchers can now control two quantum light sources rather than one. Trivial as it may seem to those uninitiated in quantum, this colossal breakthrough allows researchers to create a phenomenon known as quantum mechanical entanglement. This in turn, opens new doors for companies and others to exploit the technology commercially.

Going from one to two is a minor feat in most contexts. But in the world of quantum physics, doing so is crucial. For years, researchers around the world have strived to develop stable quantum light sources and achieve the phenomenon known as quantum mechanical entanglement—a phenomenon, with nearly sci-fi-like properties, where two light sources can affect each other instantly and potentially across large geographic distances.

Entanglement is the very basis of quantum networks and central to the development of an efficient quantum computer.

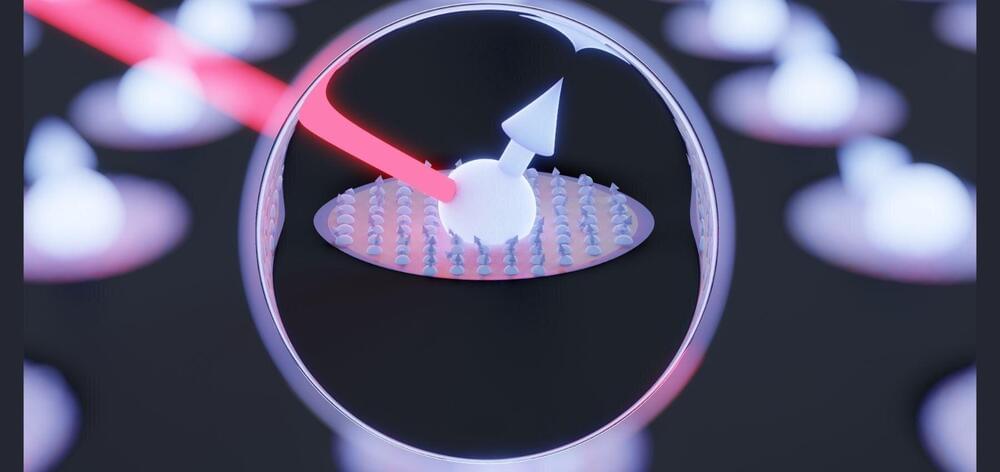

An international team of scientists have demonstrated a leap in preserving the quantum coherence of quantum dot spin qubits as part of the global push for practical quantum networks and quantum computers.

These technologies will be transformative to a broad range of industries and research efforts: from the security of information transfer, through the search for materials and chemicals with novel properties, to measurements of fundamental physical phenomena requiring precise time synchronization among the sensors.

Spin-photon interfaces are elementary building blocks for quantum networks that allow converting stationary quantum information (such as the quantum state of an ion or a solid-state spin qubit) into light, namely photons, that can be distributed over large distances. A major challenge is to find an interface that is both good at storing quantum information and efficient at converting it into light.