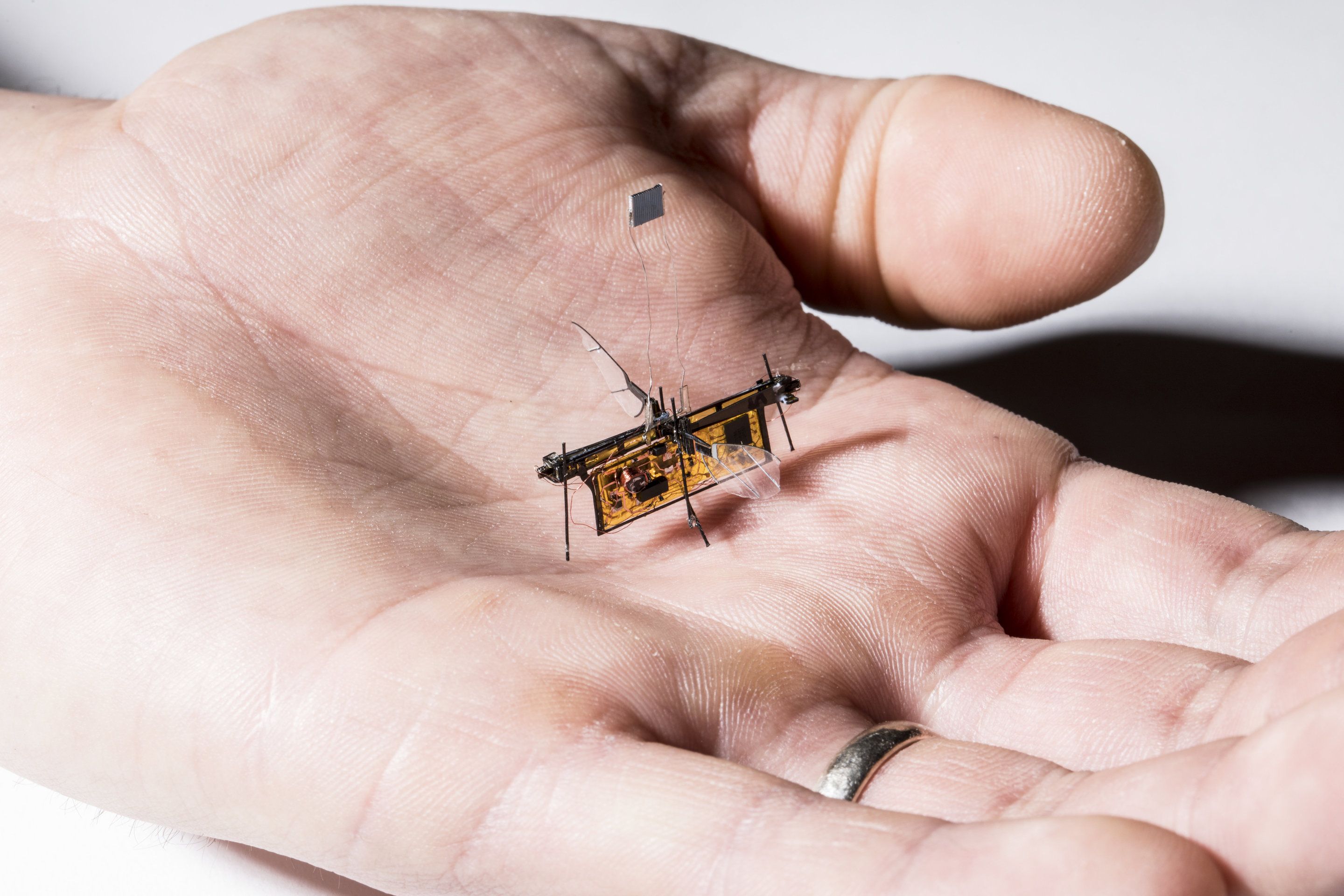

Insect-sized flying robots could help with time-consuming tasks like surveying crop growth on large farms or sniffing out gas leaks. These robots soar by fluttering tiny wings because they are too small to use propellers, like those seen on their larger drone cousins. Small size is advantageous: These robots are cheap to make and can easily slip into tight places that are inaccessible to big drones.

But current flying robo-insects are still tethered to the ground. The electronics they need to power and control their wings are too heavy for these miniature robots to carry.

Now, engineers at the University of Washington have for the first time cut the cord and added a brain, allowing their RoboFly to take its first independent flaps. This might be one small flap for a robot, but it’s one giant leap for robot-kind. The team will present its findings May 23 at the International Conference on Robotics and Automation in Brisbane, Australia.

Who among us remember “Prey” by Michael Chichton. A swarm of these electronic flying bugs were mesh-networked together and drew power from sunlight. (At night, the swarm lost coherence and collapsed to the ground). But during coherence, they eventually gained sentience with goals that did not allign with their human creators. (And there lies a plot)!

To communicate with humans, the swarm would assemble into a single human-shaped android and fashion temporary vocal chords from their constituant flea-sized robots. Crichton did a terrific job of explaining how the bot would occassionally go fuzzy (out of focus), as the micro-constituents lost repositioned or compensated for communication delays.