Jan 9, 2024

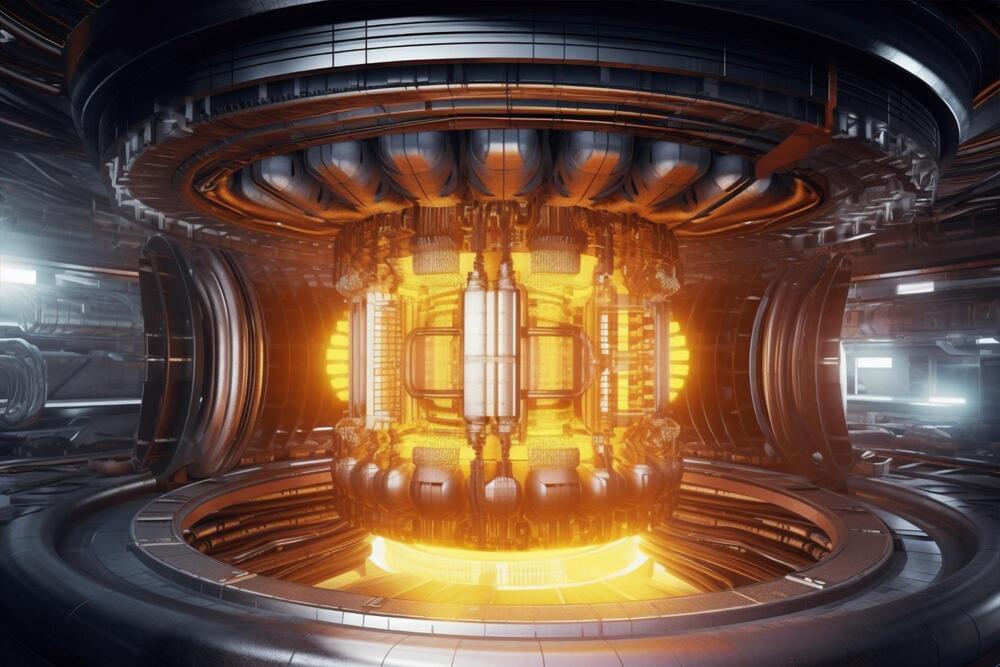

Fusing Academia and Industry: The Key to Unlocking Fusion Energy’s Potential

Posted by Saúl Morales Rodriguéz in categories: education, nuclear energy, sustainability

Fusion’s success as a renewable energy depends on the creation of an industry to support it, and academia is vital to that industry’s development.

A new study suggests that universities have an essential role to fulfill in the continued growth and success of any modern high-tech industry, and especially the nascent fusion industry; however, the importance of that role is not reflected in the number of fusion-oriented faculty and educational channels currently available. Academia’s responsiveness to the birth of other modern scientific fields, such as aeronautics and nuclear fission, provides a template for the steps universities can take to enable a robust fusion industry.

Insights from Experts.