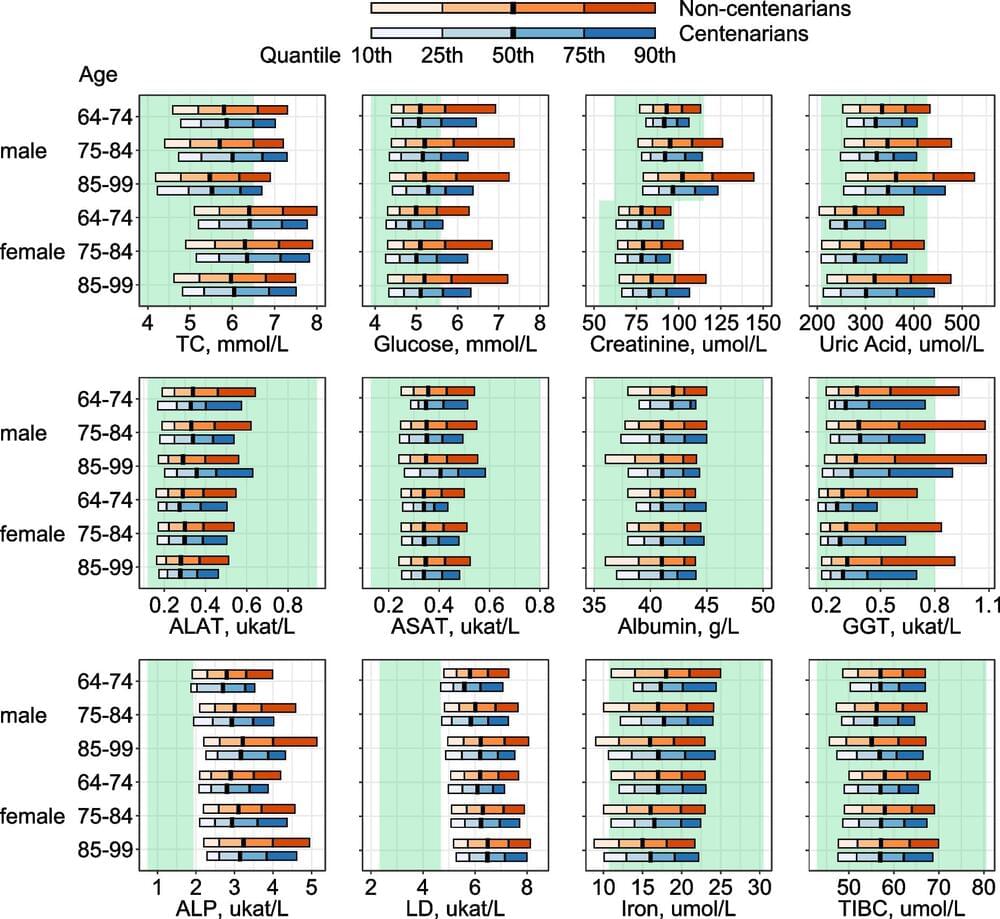

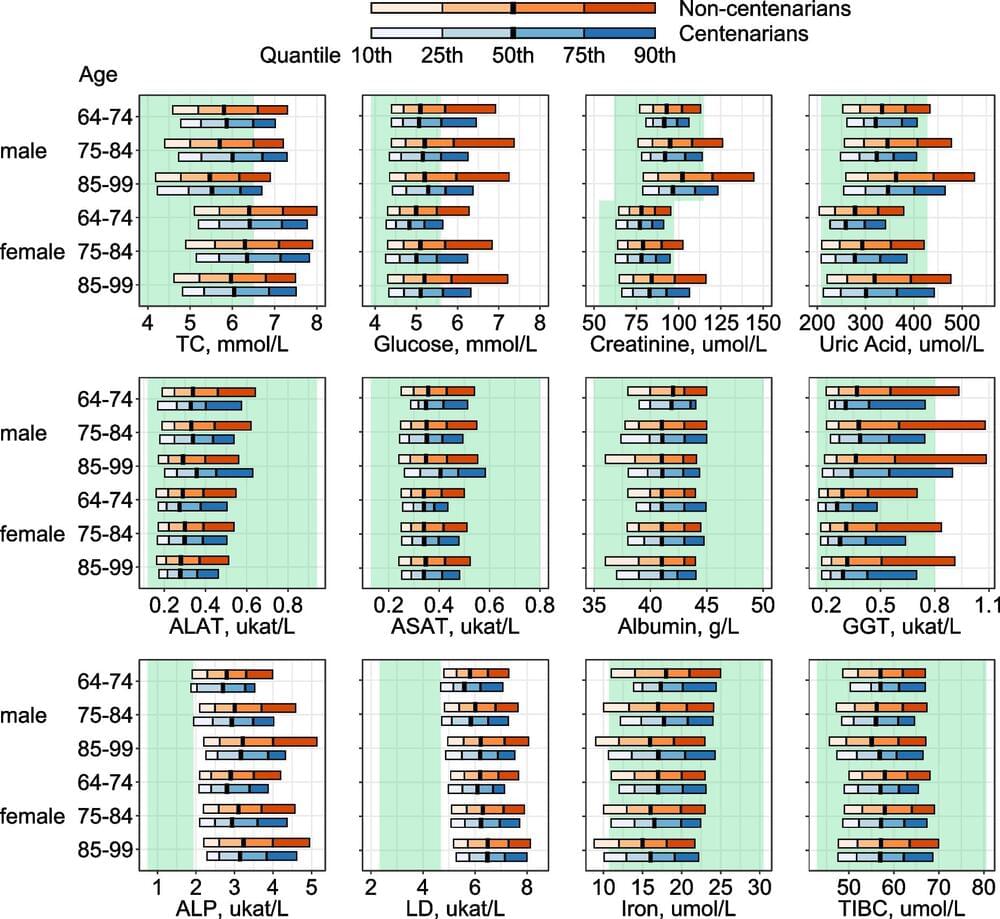

Knowledge of how centenarians’ biomarker profiles differ from those of non-centenarians at comparable ages already earlier in life is scarce. The lack of suitable, large prospective data with long follow-up is one likely reason for this. The Japanese cohort mentioned above included individuals aged 85+ only, and more than half of them were already centenarians at baseline enrollment. Since health selection likely starts even earlier than age 85, it is important to examine potential differences between long-lived individuals and those with average life spans already several years before—or during the process of—health deterioration.

Moreover, several studies have reported that centenarians are not such a homogeneous population as sometimes perceived. An Italian study based on 602 centenarians identified three subgroups with distinct health profiles [11]. It was found that 20% of the centenarians were in good health, 33% had intermediate health status, and 47% were in poor health. A Danish study also detected three distinct subgroups defined by health status: robust, intermediate, and frail centenarians [12]. About half of the Danish centenarians were in the “robust” group. A German study using health insurance data from 1,121 centenarians found four distinct comorbidity profiles, and only a small proportion of centenarians had a low morbidity burden [13]. These findings raise the question of whether such heterogeneity in centenarians’ health profiles is already visible earlier in life and, for example, reflected in their biomarker profiles. Uncovering potential heterogeneity in such profiles more than one decade ago may help us understand characteristics of health trajectories associated with exceptional longevity.

The AMORIS (Apolipoprotein MOrtality RISk) cohort offers a unique opportunity to compare biomarkers measured at similar ages but earlier in life between centenarians and their shorter-lived peers. The cohort contains a variety of biomarkers assessed approximately 30 years ago and was linked to several administrative health registers with data until 2020. Using these data, we aim to (i) describe biomarker profiles earlier in life among individuals eventually becoming centenarians and their shorter-lived peers, (ii) investigate the association between a set of biomarkers and the chance of reaching age 100 with up to 35 years of follow-up, and (iii) investigate differences in biomarker profiles within the centenarian population.